Social and Psychological Influences on Appetite and Eating Behaviors

- Bobby Cheon,

PhD, Stadtman Investigator, Social and Behavioral Sciences Branch, DiPHR - Julia Bittner, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Aleah Brown, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Nitya Kari, BA, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Matthew Siroty, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

There are widespread socioeconomic disparities in diet-related disorders, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. Children and adults from households of disadvantaged socioeconomic status (e.g., lower income or social standing) experience higher incidences of these disorders. Socioeconomic disadvantage may impose barriers to accessing healthier diets and lifestyles, as well as influencing psychological processes that guide food choices and eating behaviors. Our aim is to identify psychological mechanisms involved in the emergence of these diet-related health disparities. We examine psychological determinants of food preferences, eating behaviors, and the regulation of appetite, and how these processes may be shaped by social factors such as the experience of disadvantaged socioeconomic status. We apply both experimental and population-health approaches to investigate how such vulnerabilities influence food-related preferences, behaviors and health across development. Through this work, we seek to: (1) identify social factors that contribute to obesogenic eating behaviors; (2) enhance prediction of which children have higher risk of (or resilience against) developing obesity and cardiometabolic disorders later in life; and (3) inform the development of interventions that can reduce disparities in these disorders.

Contributions of socioeconomic mobility to dietary patterns and metabolic health

Although lower childhood and adulthood socioeconomic status (SES) has been linked to poorer diet quality, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, it remains unclear whether the trajectory of socioeconomic status one experiences from childhood into adulthood (socioeconomic mobility) contributes to these outcomes. Socioeconomic mobility may impact adult health through changes in the financial resources available to engage in healthier lifestyles and through psychological strain related to changing status. One understudied pathway potentially linking socioeconomic mobility with health is through changes in an individual’s perceptions of their SES compared with others (subjective SES). Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), our analysis investigated whether subjective SES contributes to associations of socioeconomic mobility with metabolic health (body mass index, metabolic syndrome) and unhealthy diets (high fast-food and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption). We found that participants who experienced substantial upward mobility between adolescence and mid-adulthood had a lower risk of high sugar-sweetened beverage consumption than did those who had consistently low SES from adolescence to adulthood. Additionally, higher subjective SES mediated associations between upward (but not downward) mobility and lower risks of metabolic syndrome, high fast-food consumption, and high sugar-sweetened beverage consumption [Reference 1]. Overall, upward mobility was associated with higher subjective SES and lower risks of poor metabolic and dietary outcomes. Our findings suggest that, while upward mobility may provide more financial and material resources to support better diets and metabolic health, psychological experiences linked to upward mobility also play a unique role in this process and could be a target of future interventions to reduce disparities in metabolic health.

Our group is currently investigating the relationships between socioeconomic mobility, subjective SES, and adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm birth. We are also examining the effects of low subjective SES on food preferences and eating behaviors during pregnancy, which builds upon our team’s prior findings that lower subjective SES experienced in early life is predictive of higher odds of gestational diabetes in adulthood [Reference 2].

The interplay between subjective social status and social stressors on child eating behaviors and adiposity

Children are frequently exposed to diverse social stressors, such as teasing and social exclusion. Such social stressors and subordinate social status have been independently associated with an increased body mass index (BMI) and overeating among children. However, children experiencing lower perceived social standing than peers may be especially vulnerable to the negative effects of social stressors such as teasing and exclusion. We had previously found that children who perceive their families as having lower social standing and were from lower SES households were more likely to exhibit excessive preoccupation with food and eating (hyperphagia) [Reference 5]. However, the interplay between lower perceived social standing and exposure to common social stressors, such as teasing, on child eating behaviors and adiposity remain unclear.

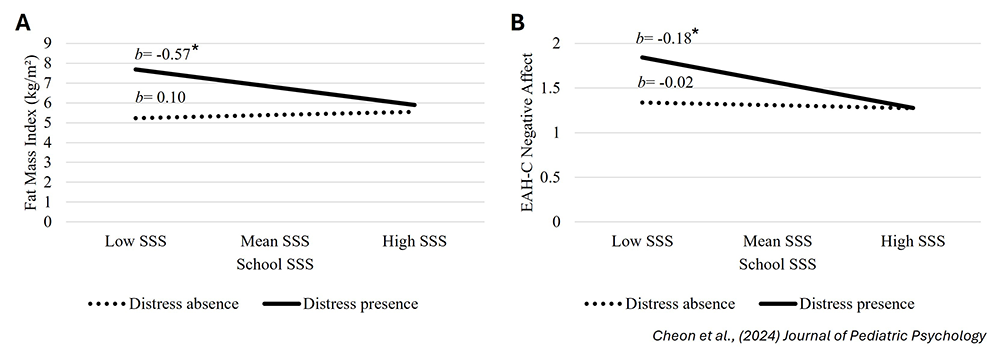

In collaboration with NICHD’s Children’s Growth and Behavior Study (NCT02390765), we tested the statistical interaction of subjective social status (perceived social standing compared with peers) and distress from being teased on BMI Z-scores, adiposity (fat-mass index), and the tendency to eat in the absence of hunger among children and adolescents (ages 8 to 17 years). We observed that teasing distress was associated with greater BMI Z-scores, adiposity, and child-reported eating in the absence of hunger as a result of negative affect, but there were no associations of subjective social status with these outcomes. However, there was a statistical interaction between subjective social status and teasing distress on BMI Z-scores, adiposity, and eating in the absence of hunger resulting from negative affect, such that subjective social status was negatively associated with these outcomes only among children reporting distress from teasing (Figure 1) [Reference 3]. These findings suggest that the relationship between lower subjective social status and increased adiposity and overeating behaviors may be exacerbated by other threats to social standing, such as teasing.

Figure 1. Lower subjective social status is associated with greater adiposity and eating in the absence of hunger among children experiencing teasing distress.

Interactions of subjective social status (SSS) and teasing distress on: A. fat-mass index (n = 114) and B. child-reported eating in the absence of hunger (EAH-C) resulting from negative affect (n = 100). Lower SSS is associated with higher fat-mass index and EAH-C resulting from negative affect only when children reported experiencing teasing distress. *p < 0.05.

Figure 1. Lower subjective social status is associated with greater adiposity and eating in the absence of hunger among children experiencing teasing distress.

Interactions of subjective social status (SSS) and teasing distress on: A. fat-mass index (n = 114) and B. child-reported eating in the absence of hunger (EAH-C) resulting from negative affect (n = 100). Lower SSS is associated with higher fat-mass index and EAH-C resulting from negative affect only when children reported experiencing teasing distress. *p < 0.05.

In other recent work, we examined whether exposure to social exclusion within a laboratory context motivates increased snack intake among children, and whether this response predicts future BMI. In collaboration with the Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) Study, we exposed children (8.5 years old) to a situation in which they were led to believe that two other children were excluding them from a computerized ball-tossing game. Heart rate variability was monitored during the game to measure physiological stress responses to social exclusion. Following the game, children were provided with various snack foods that they could consume ad-libitum. We found that greater stress response to social exclusion was associated with increased energy intake from the snack, but this effect was only observed among children who reported higher levels of social anxiety [Reference 4]. Importantly, the pattern of increased snack consumption following stress from social exclusion among this group of children predicted higher BMI Z-scores 1.5 years later (at age 10). The findings suggest that, among children who experience higher anxiety related to social situations, a pattern of snacking in response to stress from social exclusion may contribute to increased body mass.

Overall, these recent studies provide novel insights that children exposed to multiple social adversities (e.g., low subjective social status and teasing) may be more susceptible to overeating and at greater risk for obesity than are children who may experience a single form of social adversity. Consequently, efforts to identify and intervene on the social and behavioral determinants of obesity should consider the interplay of multiple social stressors. Our team is currently investigating potential mechanisms by which lower subjective social status may be motivating greater energy intake among children, such as by disrupting sensations of satiation and satiety.

Additional Funding

- K99/R00 Pathway to Independence Award to Julia Bittner

- NICHD Early Career Award to Julia Bittner

Publications

- Socioeconomic mobility, metabolic health, and diet: mediation via subjective socioeconomic status. Obesity 2024 32:2035–2044

- Relationships between early-life family poverty and relative socioeconomic status with gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy later in life. Ann Epidemiol 2023 86:8–15

- Lower subjective social status is associated with increased adiposity and self-reported eating in the absence of hunger due to negative affect among children reporting teasing distress. J Pediatr Psychol 2024 49:462–472

- The effects of acute social ostracism on subsequent snacking behavior and future body mass index in children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2024 48:867–875

- Independent and interactive associations of subjective and objective socioeconomic status with body composition and parent-reported hyperphagia among children. Child Obes 2023 20:394–402

Collaborators

- Zhen Chen, PhD, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Branch, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Ciarán Forde, PhD, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- Stephen Gilman, ScD, Social and Behavioral Sciences Branch, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Jennifer Howell, PhD, University of California Merced, Merced, CA

- Albert Lee, PhD, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

- Tonja Nansel, PhD, Social and Behavioral Sciences Branch, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Aimee Pink, PhD, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore

- Jack Yanovski, MD, PhD, Section on Growth and Obesity, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

Contact

For more information, email bobby.cheon@nih.gov or visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/dir/dph/officebranch/sbsb.