You are here: Home > Section on Gene Expression

Control of Gene Expression During Development

- Judith A. Kassis, PhD, Head, Section on Gene Expression

- J. Lesley Brown, PhD, Staff Scientist

- Yuzhong Cheng, PhD, Senior Research Technician

- Melissa Cunningham, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Kristofor Langlais, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Katherine Benson, Summer Student

During development and differentiation, genes either become competent to be expressed or are stably silenced in an epigenetically heritable manner. This selective activation/repression of genes leads to the differentiation of tissue types. Recent evidence suggests that modifications of histones in chromatin contribute substantially to determining whether a gene will be expressed. Our group is interested in understanding how chromatin-modifying protein complexes are recruited to DNA. In Drosophila, two groups of genes, the Polycomb group (PcG) and Trithorax group (TrxG), are important for inheritance of the silenced and active chromatin state, respectively. Regulatory elements called Polycomb group response elements (PRE) are cis-acting sequences required for the recruitment of chromatin-modifying PcG protein complexes. TrxG proteins may act through either the same or overlapping cis-acting sequences. Our group aims to understand how PcG and TrxG proteins are recruited to DNA. We are also interested in how distantly located transcriptional enhancer elements are able to selectively activate a promoter that may be tens (or even hundreds) of kilobases away. Our data suggest that promoter-proximal elements, some of which overlap with PREs, impart specificity to promoter–enhancer communication.

Polycomb response elements

Polycomb response elements (PREs) are DNA elements through which the PcG protein transcriptional repressors act. Many of the PcG proteins are associated in two protein complexes that repress gene expression by modifying chromatin. Both these complexes specifically associate with PREs in vivo; however, it is not known how they are recruited or held at the PRE. PREs are complex elements harboring binding sites for many proteins. Our laboratory has been working to define all the sequences and DNA-binding proteins required for the activity of a 181-bp PRE from the Drosophila gene encoding engrailed (en). At least seven DNA-binding sites contribute to the activity of this 181-bp PRE. One of the required binding sites is for the Polycomb-group proteins Pleiohomeotic (Pho) and Pleiohomeotic-like (Phol). Binding sites for the proteins GAGA factor, Pipsqueak, Zeste, and Dsp1 also are present within the en PRE. Proteins that bind to two other sites remain unidentified. Our laboratory found that members of the Sp1/KLF family of zinc-finger proteins bind to another required binding site (Brown et al., Nucleic Acid Res 2005;33:5181). This family of proteins encodes transcription factors and has undergone extensive study in mammals—there are 20 Sp1/KLF family members in mammals. Drosophila has 9 Sp1/KLF family members, of which eight bind to the en PRE. We derived a consensus binding site for the Sp1/KLF Drosophila family members and showed that the consensus sequence is present in most of the molecularly characterized PREs. The data suggest that one or more Sp1/KLF family members play a role in PRE function in Drosophila.

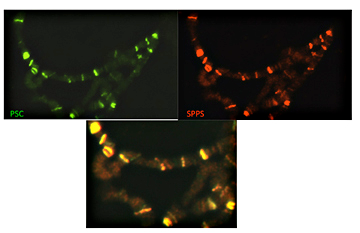

Figure 1. Spps and Psc colocalize on polytene chromosomes

Polytene chromosomes were fixed and incubated with antibodies against Psc (green) and Spps (red). The lower panel shows that these two proteins completely co-localize on these chromosomes.

We have been working to determine which of the Sp1/KLF family members in Drosophila may be involved in PcG function. We made antibodies to the three most likely candidates. We found that one of these proteins, Spps, binds to Drosophila polytene chromosomes in a pattern that completely overlaps that of the Polycomb protein Psc (Figure 1). Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments showed that Spps binds to PREs. These data strongly suggest that Spps plays a role in Polycomb group repression. Using homologous recombination, we deleted the Spps gene and showed that it is required for Polycomb group repression late in development. Finally, we showed that a mutation in Spps enhances the phenotype of Pho mutants, strongly suggesting that Spps and Pho work together to recruit Polycomb group complexes to the DNA (4).

Although much is known about the protein-binding sites required for PRE function, we are not able to predict the location of a PRE based on the presence of binding sites alone. To help us identify either other protein-binding sites required for PRE function or other important characteristics of PREs (such as the number or spacing of binding sites), we have begun to analyze other PREs from the en region of the genome. To this end, we characterized two PREs from inv (which encodes invected), a gene that is co-regulated with en (2). Our work should lead to a better understanding of the protein-binding sites required for PRE function.

Understanding the role of PREs and flanking sequences at the en gene

The Drosophila en gene encodes engrailed, a homeodomain protein that plays an important role in the development of many parts of the embryo, including formation of the segments, nervous system, head, and gut. The gene also plays a particularly significant role in the development of the adult, specifying the posterior compartment of each imaginal disk. Accordingly, en is expressed in a highly specific and complex manner in the developing organism. We have been studying the 181-bp en PRE, which is located near the en promoter from −576 to −395 upstream of the transcription start site. We were interested in determining the role of this PRE in the control of en expression. One of our first findings demonstrated that this PRE is redundant with other flanking PREs in the endogenous en gene; another strong PRE is located from −1100 to −1500, and probably other weak PREs are located nearby. In fact, when we examined the location of Ph and Pho proteins on en DNA by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we found that they are bound to a 2.5 kb region extending from the en promoter to about −2.5kb upstream. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that a 500-bp deletion that includes the 181-bp PRE and flanking sequence did not lead to ectopic en expression. The remaining PREs were apparently sufficient to recruit PcG proteins. However, we were surprised that loss of the DNA led to a loss-of-function phenotype, suggesting that the DNA must also play a positive role in the expression of en . Results of our current work suggest that this is attributable to the loss of a promoter-proximal tethering element (see below). In other experiments, we were able to show that PREs can either activate or repress transcription in a context-dependent manner. Further, our data suggest that PREs mediate looping between distant enhancers and the en promoter. Our experiments suggest activities of PREs not foreseen by others in the field.

The regulatory sequences for the en gene extend over a 70-kb region. Our laboratory has used reporter constructs to find sequences important for expression in stripes, the nervous system, and head, among others. Discrete regulatory elements are located throughout the 70-kb region. We also found at least seven additional potential PREs located throughout the region. Others have shown that PcG protein complexes bring together DNA fragments in vitro, and it is also possible that the complexes cause looping in vivo. We are interested in learning whether the additional PREs are involved in mediating interactions between distant enhancers and the en promoter.

The en gene exists in a gene complex with the nearby gene encoding invected (inv). These two genes are co-regulated, and express proteins with largely redundant proteins. By studying the regulation of en and inv , we are trying to understand how regulatory sequences up to 80 kb away regulate the activity of two promoters.

A genetic screen reveals the inhibitory effect of transcriptional activators on PRE activity.

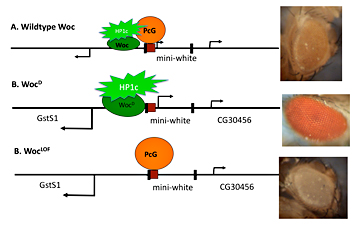

Figure 2. Amount of activator present influences Polycomb group repression

A model depicting the effect of competition between the activator Woc-HP1c and the repressor PcG proteins on the expression of the mini-white gene. The mini-white gene is encoded on a transgene that has a PRE (red box) upstream and is flanked by P-element ends (black boxes). The two genes that flank the mini-white transgene, GstSt and CG30465, are also shown. In wild type, Woc-HP1c and PcG co-exist to give a low level of mini-white transcription and a yellow eye color. In the wocD mutant, more HP1c is recruited, leading to a loss of PcG protein repression, a higher level of mini-white transcription, and a red eye color. In a woc loss-of function mutant (LOF), no HP1c is recruited, and PcG proteins silence the transcription of mini-white, leading to a white eye color.

We performed a genetic screen hoping to identify new members of the Trithorax group and Polycomb group. The generation of transgenic Drosophila relies on an eye color gene, white, to detect transgenic flies. Eye color is dependent on the expression level of the white gene; more expression of white causes a darker eye color whereas less expression causes a lighter eye color. PREs linked to white (a PRE–white transgene) cause less white expression, leading to a lighter eye color. We performed a genetic screen to identify mutations that darken the eye color of transgenic flies with a PRE–white transgene. We reasoned that mutation of a PcG gene that encodes a repressor might lead to a darkening of the eye color. Increasing the activity of an activator protein (a potential Trithorax-group gene) might also darken the eye color through competition with the PcG repressors. We screened over 60,000 flies and obtained nine mutants. We have now characterized two of the mutants and describe one below.

We obtained a dominant mutation in the transcriptional activator Woc. As shown by others, Woc stimulates transcription through an interaction with the protein HP1c. Our mutant Woc[D] contains a single amino acid change, which leads to an increase in transcriptional activity of this protein. Our results suggest that increasing the activity of Woc reduces the ability of PcG repressors to act (Figure 2). The data point to the interplay between repressors and activators in setting the correct expression levels of genes.

Enhancer-promoter communication

Enhancers are often located tens or even hundreds of kilobases away from their promoter, sometimes even closer to promoters of genes other than the one they should activate. We have shown that en enhancers can act over large distances, even skipping over other transcription units, choosing the en promoter over those of neighboring genes. This specificity is achieved in at least three ways. First, early-acting en stripe enhancers exhibit promoter specificity. Second, a proximal promoter-tethering element is required for the action of the imaginal disk enhancer(s). Our data suggest that there are two partially redundant promoter-tethering elements. Third, the long-distance action of en enhancers requires a combination of the en promoter and sequences within or closely linked to the promoter-proximal Polycomb-group response elements. These data show that multiple mechanisms ensure proper enhancer-promoter specificity at the Drosophila en locus and provide one of the first detailed views of how promoter-enhancer specificity is achieved (1).

Publications

- Kwon D, Mucci D, Langlais KK, Americo JL, DeVido SK, Cheng Y, Kassis JA. Enhancer-promoter communication at the Drosophila engrailed locus. Development 2009 136:3067-3075.

- Cunningham MD, Brown JL, Kassis JA. Characterization of the Polycomb group response elements of the Drosophila melanogaster invected locus. Mol Cell Biol. 2010 30:828-830.

- Kassis JA, Kennison JA. Recruitment of Polycomb complexes: A role for Scm. Mol Cell Biol. 2010 30:2581-2583.

- Brown JL, Kassis JA. Spps, a Drosophila Sp1/KLF family member, binds to PREs and is required for PRE activity late in development. Development 2010 137:2597-2602.

Collaborators

- James A. Kennison, PhD, Program in Genomics of Differentiation, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

Contact

For more information, email jk14p@nih.gov.