Genomics of Development in Drosophila

- James A. Kennison, PhD, Head, Section on Drosophila Gene Regulation

- Monica T. Cooper, BA, Senior Research Technician

- Jasmine Wong, BA, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

Our goal is to understand how linear information encoded in genomic DNA functions to control cell fates during development. The Drosophila genome is about one twentieth the size of the human genome. However, despite its smaller size, most developmental genes and at least half of the disease- and cancer-causing genes in man are conserved in Drosophila, making Drosophila an excellent model system for the study of human development and disease. One of the important groups of conserved developmental genes are the homeotic genes. In Drosophila, the homeotic genes specify cell identities at both embryonic and adult stages. The genes encode homeodomain-containing transcription factors that control cell fates by regulating the transcription of downstream target genes. The homeotic genes are expressed in precise spatial patterns that are crucial for the proper determination of cell fate. Both loss of expression and ectopic expression in the wrong tissues lead to changes in cell fate. The changes provide powerful assays for identifying the trans-acting factors that regulate the homeotic genes and the cis-acting sequences through which they act. The trans-acting factors are also conserved between Drosophila and human and have important functions, not only in development but also in stem-cell maintenance and cancer.

Cis-acting sequences for transcriptional regulation of the Sex combs reduced (Scr) homeotic gene

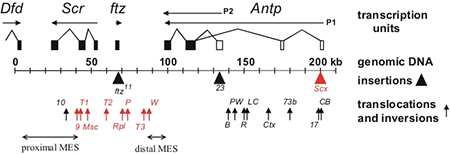

Assays in transgenes in Drosophila previously identified cis-acting transcriptional regulatory elements from homeotic genes. The assays identified tissue-specific enhancer elements as well as cis-regulatory elements that are required for the maintenance of activation or repression throughout development. While these transgenic assays have been important in defining the structure of the cis-regulatory elements and identifying trans-acting factors that bind to them, their functions within the context of the endogenous genes remain poorly understood. We used a large number of existing chromosomal aberrations in the Scr homeotic gene to investigate the functions of the cis-acting elements within the endogenous gene. The chromosomal aberrations identified an imaginal leg enhancer about 35 kb upstream of the Scr promoter. The enhancer is not only able to activate transcription of the Scr promoter that is 35 kb distant but can also activate transcription of the Scr promoter on the homologous chromosome. Although the imaginal leg enhancer can activate transcription in all three pairs of legs, it is normally silenced in the second and third pairs of legs. The silencing requires the Polycomb-group proteins. We are currently attempting to identify the cis-regulatory DNA sequences in the Scr that are required for Polycomb-group silencing in the second and third legs. Characterization of the chromosomal rearrangements shown in Figure 1 also revealed that two genetic elements (proximal and distal MES [maintenance elements for silencing]), about 70 kb apart in the Scr gene, must be in cis to maintain proper repression. When not physically linked, the elements interact with elements on the homologous chromosome and cause derepression of its wild-type Scr gene. Using a transgenic assay, we identified at least five DNA fragments from the Scr gene that silence transcription from a reporter gene. The transcriptional silencers are clustered in the two regions whose interactions are required for the maintenance of silencing in the endogenous genes. We also use the silencer elements to screen for mutations in trans-acting silencing factors.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 1. Chromosomal aberrations in the distal half of the Antennapedia complex

The transcription units are shown above the genomic DNA, while chromosomal aberrations are shown below (solid triangles indicate insertions of transposable elements and upward arrows indicate breakpoints of translocations and inversions). Chromosomal aberrations (red) interfere with silencing in the adult second and third legs. The regions that include the proximal and distal MES are indicated by horizontal arrows.

Trans-acting activators and repressors of homeotic genes

The initial domains of homeotic gene repression are set by the segmentation proteins, which also divide the embryo into segments. Genetic studies identified the trithorax group of genes that are required for expression or function (such as maintenance of transcriptional activation) of the homeotic genes. Maintenance of transcriptional repression requires the proteins encoded by the Polycomb-group genes. To identify new trithorax-group activators and Polycomb-group repressors, we screened for new mutations that mimicked the following phenotypes: loss of function or ectopic expression of the homeotic genes. We generated over 4,000 lethal mutants and, among those that die late in development, identified two dozen mutants with homeotic phenotypes. Some of the homeotic phenotypes are shown in Figure 2. The mutants identify genes required for expression or function of the homeotic genes.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 2. Homeotic phenotypes of new pharate-adult lethal mutants

A) Wild-type on the left and the transformation of aristae to distal leg on the right. B) Wild-type haltere on the left and transformations of anterior and posterior haltere to anterior and posterior wing in the middle and right, respectively. C) First legs from a wild-type male on the left and three different mutants with reduced sex combs on the right. D) Mutant male with sex combs on both the first and second tarsal segments. E) Mutant male with sex combs on all three pairs of legs. F) Abdominal segments from a wild-type male on the left; mutant male with transformation of the fifth abdominal segment to a more anterior identity on the right.

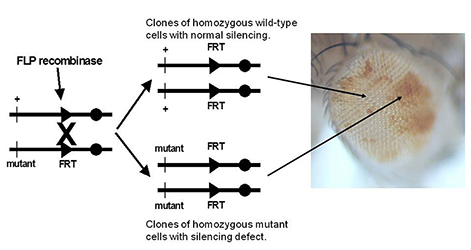

We also use Polycomb-group response elements from the Scr gene to screen for recessive Polycomb-group mutations. Transgenes with a Polycomb-group response element and a reporter gene (the Drosophila mini-white gene) exhibit reporter gene expression in flies heterozygous for the transgene, but reporter gene expression is repressed in flies homozygous for the transgene. In flies homozygous for transgenes with the mini-white reporter gene silenced by the Polycomb-group response elements, we generate clones of cells in the eye that are homozygous for newly induced mutations, using the yeast FLp/FRT site-specific recombination system (Figure 3). Silencing mutations are detected by the appearance of pigmented spots in the white-eyed flies (cells that derepress the silenced mini-white reporter gene). We screened about 98% of the genome and recovered 342 new silencing mutants. About one third of the new mutants do not carry a new silencing mutation but bear chromosome aberrations that generate aneuploid cells after mitotic recombination. The aneuploid regions include the reporter transgene and they disrupt silencing by changing copy number. Although the mutants do not identify new genes, the phenomenon that we discovered will be very useful for detecting chromosomal aberrations in F1 mutant screens. The remaining two thirds of our mutants are not associated with large chromosomal aberrations and carry mutations in genes required for Polycomb-group transcriptional silencing. Seventy-seven mutations are in 14 known Polycomb-group genes. The remaining mutations identify 61 additional genes required for silencing. For 44 of these genes, we identified the corresponding transcription units using a combination of meiotic recombination mapping and whole-genome sequencing. The new silencing genes include DNA–binding proteins, chromatin-remodeling factors, and insulator proteins.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 3. Genetic screen for new mutations that disrupt pairing-sensitive silencing

Flies homozygous for transposons carrying the mini-white reporter gene and a pairing-sensitive silencing element have white eyes. Clones of cells homozygous for newly induced mutants are generated using the yeast site-specific recombinase (FLP recombinase) and its target site (FRT). The clones of mutant cells are able to express the mini-white reporter gene and are pigmented (shown in the eye on the right of the figure).

Structure and function of the Drosophila genome

The Drosophila melanogaster genome has been intensely studied for over 100 years. Recently, sequencing of the majority of the genomic DNA revealed much about the structure and organization of the genome. Despite those molecular advances, much remains to be discovered about the functions encoded within the genome. As part of a long-term project to understand the function and organization of the Drosophila genome, we set out to identify all genes essential for viability or male fertility in two regions of the genome that span almost 1 megabase of DNA (shown in Figures 4 and 5). We identified 10 gene clusters that appear to have arisen by tandem duplication. The clusters include 34 of the 137 predicted genes. We identified 47 genes essential for zygotic viability, including two of the pairs of tandemly duplicated genes. We identified the transcription units corresponding to all genes essential for viability. We also identified eight genes that are required only for fertility, most of which are male-specific in expression. The transcription units corresponding to all the genes required for fertility have been identified. With the exception of the Antennapedia and bithorax homeotic gene complexes, for no other regions of the Drosophila genome have transcription units essential for viability and fertility been as completely analyzed.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 4. Molecular map of the genomic region deleted in Df(3L)th102 (polytene region 72A-D)

The approximately 320 kb of genomic DNA (from 3L: 15918k to 16240k, Release 5.23) is represented by the horizontal black arrow at the top. The annotated transcription units are represented by colored thick horizontal arrows. Transcription units essential for viability are red and orange. Transcription units essential only for male fertility are blue and the transcription unit required for female fertility is purple. The clusters of transcription units encoding related proteins are yellow and orange [the l(3)72Dp and l(3)72Dr genes essential for viability]. The remaining protein-coding genes are black, and the tRNAs, mirRNAs, and non-coding RNAs are green. The non-essential DNA missing in flies trans-heterozygous for the overlapping deletions Df(3L)Exel6128 and Df(3L)BSC559 and the putative “gene desert” are indicated by the horizontal black bars at the bottom.

We were also able to assess the progress of the Drosophila Gene Disruption Project. While the project has tagged about two-thirds of the annotated genes with transposon insertions, the insertions disrupt the function of only 45% of the genes. Our analysis of data from the Drosophila modENCODE project suggests that 20% or more of the genome is expressed only in males, consistent with the observations that male-sterile mutations are recovered at almost 15% the frequency of lethal mutations. In contrast, only about 1–2% of the genome is expressed only in females.

Surprisingly, when we deleted a genomic region that spanned 55 kb, we found no effects on either viability or fertility. Although this nonessential region includes seven predicted genes, there is no evidence that the genes are expressed under any known conditions. The seven predicted genes are also not evolutionarily conserved. While there are no evolutionarily conserved open reading frames within this gene desert, the region has 48 DNA sequences of between 12 and 33 base pairs that are each identical in 12 different Drosophila species. The strong conservation indicates that the sequences must have some function that is beneficial to flies living outside the laboratory.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 5. Molecular map of the genomic region deleted in Df(3L)kto2 (polytene region 76B-D)

The approximately 640 kb of genomic DNA (from 3L: 19291k to 19926k, Release 5.23) is represented by the horizontal black arrow at the top. The annotated transcription units are represented by colored thick horizontal arrows. Transcription units essential for viability are red and orange. Transcription units essential only for fertility are blue (male-specific) and purple (both sexes). The clusters of transcription units encoding related proteins are gold, brown, and orange (the verm and serp genes essential for viability). The remaining protein-coding genes are black, and the tRNAs, mirRNAs, and non-coding RNAs are green. A 31.4 kb tandem duplication (distal copy and proximal copy) flanked by Doc transposable elements in the sequenced iso-1 strain (but not in other wild-type strains) is shown on the genomic DNA, with the Doc elements represented by inverted brown triangles. The non-essential DNA missing in flies trans-heterozygous for the overlapping deletions Df(3L)Exel9007 and Df(3L)ED4799 is indicated by the horizontal black bar at the bottom.

Publications

- Monribot-Villanueva J, Juarez-Uribe RA, Palomera-Sanchez Z, Gutierrez-Aguiar L, Zurita M, Kennison JA, Vazquez M. TnaA, an SP-RING protein, interacts with Osa, a subunit of the chromatin remodeling complex BRAHMA and with the SUMO pathway in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One 2013; 8:e62251.

- Lindsley DL, Roote J, Kennison JA. Anent the genomics of spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One 2013; 8:e55915.

- Gilliland WD, May DP, Colwell EM, Kennison JA. A simplified strategy for introducing genetic variants into Drosophila compound autosome stocks. G3 2016; 6:3749–3755.

Collaborators

- William Gilliland, PhD, DePaul University, Chicago, IL

- Judith Kassis, PhD, Section on Gene Expression, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Dan Lindsley, PhD, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA

- Martha Vazquez, PhD, Instituto de Biotecnología, UNAM, Cuernavaca, Mexico

- Mario Zurita, PhD, Instituto de Biotecnología, UNAM, Cuernavaca, Mexico

Contact

For more information, email kennisoj@mail.nih.gov.