Molecular Genetics of an Imprinted Gene Cluster on Mouse Distal Chromosome 7

- Karl Pfeifer, PhD, Head, Section on Epigenetics

- Claudia Gebert, PhD, Biologist

- Apratim Mitra, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Beenish Rahat, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Christopher Tracy, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Ki-Sun Park, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Luke Brandenberger, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Daniel Flores, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

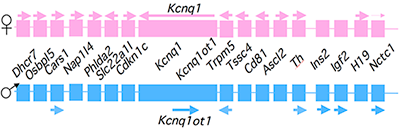

Genomic imprinting is an unusual form of gene regulation by which an allele’s parental origin restricts allele expression. For example, almost all expression of the non-coding RNA tumor suppressor gene H19 is from the maternal chromosome. In contrast, expression of the neighboring insulin-like growth factor 2 gene (Igf2) is from the paternal chromosome. Imprinted genes are not randomly scattered throughout the chromosome but rather are localized in discrete clusters. One cluster of imprinted genes is located on the distal end of mouse chromosome 7 (Figure 1). The syntenic region in humans (11p15.5) is highly conserved in gene organization and expression patterns. Mutations disrupting the normal patterns of imprinting at the human locus are associated with developmental disorders and many types of tumors, including Wilms' tumor and rhabdosarcomas in children. In addition, inherited cardiac arrhythmia is associated with mutations in the maternal-specific Kcnq1 gene. We use mouse models to address the molecular basis for allele-specific expression in this distal 7 cluster. We use imprinting as a tool to understand the fundamental features of epigenetic regulation of gene expression. We also generate mouse models for the several inherited disorders of humans, specifically models to study the effect of loss of imprinting at the Igf2/H19 locus on cardiac development, the defects in cardiac repolarization associated with loss of Kcnq1 function, and phenotypes associated with loss of Calsequestrin2 gene function.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 1. An imprinted domain on mouse distal chromosome 7

Maternal (pink, top) and paternal (blue, bottom) chromosomes are indicated. Horizontal arrows denote RNA transcription.

Alternative long-range interactions between distal regulatory elements establish allele-specific expression at the Igf2/H19 locus.

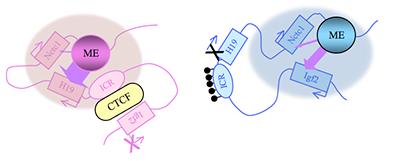

Our studies on the mechanisms of genomic imprinting focus on the H19 and Igf2 genes. Paternally expressed Igf2 lies about 80 kb upstream of the maternal-specific H19 gene. Using cell-culture systems as well as transgene and knockout experiments in vivo, we identified the enhancer elements responsible for activation of the two genes. The elements are shared and are all located downstream of the H19 gene (Figure 2).

Imprinting at the Igf2/H19 locus is dependent upon the 2.4 kb H19 imprinting control region (H19 ICR), which lies between the two genes, just upstream of the H19 promoter (Figure 2). On the maternal chromosome, binding of the CTCF protein, a transcriptional regulator, to the ICR establishes a transcriptional insulator that organizes the chromosome into loops. The loops favor H19 expression but block interactions between the maternal Igf2 promoters and the downstream shared enhancers, thus preventing maternal Igf2 expression. Upon paternal inheritance, the CpG sites within the ICR are methylated, which prevents binding of the CTCF protein, so that a transcriptional insulator is not established. Thus, paternal Igf2 promoters and the shared enhancers interact via DNA loops, and expression of paternal Igf2 is facilitated. Altogether, we find that the fundamental role of the ICR is to organize the chromosomes into alternative 3-D configurations that promote or prevent expression of the Igf2 and H19 genes.

The H19 ICR is not only necessary but is also sufficient for genomic imprinting. To demonstrate this, we used knock-in experiments to insert the 2.4 kb element at heterologous loci and demonstrated its ability to imprint these regions. Further, analyses of the loci confirmed and extended the transcriptional model described above. Upon maternal inheritance, even ectopic ICR elements remain unmethylated, bind to the CTCF protein, and form transcriptional insulators. Paternally inherited ectopic ICRs become methylated, cannot bind to CTCF, and therefore promote alternative loop domains distinct from those organized on maternal chromosomes. Most curious was the finding that DNA methylation of ectopic ICRs is not acquired until relatively late in development, after the embryo implants into the uterus. In contrast, at the endogenous locus ICR methylation occurs during spermatogenesis. The findings thus imply that DNA methylation is not the primary imprinting mark that distinguishes maternally from paternally inherited ICRs.

The Nctc1 gene lies downstream of H19 and encodes a long non-coding RNA that is transcribed across the muscle enhancer element (ME in Figure 2), which is shared by Igf2 and H19. Nctc1 expression depends on this enhancer element. Concordantly, the shared enhancer interacts with the Nctc1 promoter just as it interacts with the maternal H19 and the paternal Igf2 promoters. We showed that all three co-regulated promoters (Igf2, H19, and Nctc1) also physically interact with each other in a manner that depends on their interactions with the shared enhancer. Thus, enhancer interactions with one promoter do not preclude interactions with another promoter. Moreover, we demonstrated that these promoter-promoter interactions are regulatory; they explain the developmentally regulated imprinting of Nctc1 transcription. Taken together, our results demonstrate the importance of long-range enhancer-promoter and promoter-promoter interactions in physically organizing the genome and establishing the gene expression patterns that are crucial for normal mammalian development (References 3, 4).

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 2. Distinct maternal and paternal chromosomal conformations at the distal 7 locus

Epigenetic modifications on the 2.4 kb ICR generate alternative 3D organizations across a large domain on paternal (blue, right) and maternal (pink, left) chromosomes and thereby regulate gene expression. ICR, imprinting control region; ME, muscle enhancer; filled lollipops, CpG methylation covering the paternal ICR.

Molecular mechanisms for tissue-specific promoter activation by distal enhancers

Normal mammalian development is absolutely dependent on establishing the appropriate patterns of expression of thousands of developmentally regulated genes. Most often, development-specific expression depends on promoter activation by distal enhancer elements. The Igf2/H19 locus is a highly useful model system for investigating mechanisms of enhancer activation. First, the biological significance of the model is clear, given that expression of these genes is so strictly regulated. Even two-fold changes in RNA levels are associated with developmental disorders and with cancer. Second, we already know much about the enhancers in this region and have established powerful genetic tools to investigate their function. Igf2 and H19 are co-expressed throughout embryonic development and depend on a series of tissue-specific enhancers that lie between 8 and more than 150 kb downstream of the H19 promoter (or between 88 and more than 130 kb downstream of the Igf2 promoters). The endodermal and muscle enhancers have been precisely defined, and we generated mouse strains carrying deletions that completely abrogate enhancer function. We also generated insulator insertion mutations that specifically block muscle enhancer activity. We used these strains to generate primary myoblast cell lines so that we can combine genetic, molecular, biochemical, and genomic analyses to understand the molecular bases for enhancer functions.

A long non-coding RNA is an essential element of the muscle enhancer (Reference 4).

Transient transfection analyses define a 300–bp element that is both necessary and sufficient for maximal enhancer activity. However, stable transfection and mouse mutations indicate that this core element is not sufficient for enhancer function in a chromosomal context. Instead, the Nctc1 promoter element is also essential. (The Nctc1 gene encodes a spliced, polyadenylated long non-coding RNA). The Nctc1 RNA itself is not required (at least in trans). Instead mutational analysis demonstrates that it is Nctc1 transcription through the core enhancer that is necessary for enhancer function. Curiously, the Nctc1 promoter has chromatin features typical of both a classic enhancer and a classic peptide-encoding promoter. Several recent genomic studies also suggested a role for non-coding RNAs in gene regulation and enhancer function. We will use our model system to characterize the role of Nctc1 transcription in establishing enhancer orientation, enhancer promoter specificity, and enhancer tissue specificity.

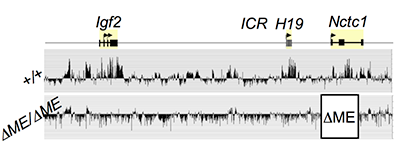

The muscle enhancer (ME) directs RNA polymerase (RNAP) II not only to its cognate promoters (i.e., to the H19 and Igf2 promoters) but also across the entire intergenic region.

We used ChIP-on-chip to analyze RNAP localization on chromatin prepared from wild-type and from enhancer-deletion (DME) cell lines (Figure 3). As expected, RNAP binding to the H19 and Igf2 promoters is entirely enhancer-dependent. Curiously, we also noted enhancer-dependent RNAP localization across the entire locus, including the large intergenic domain between the two genes. Furthermore, the RNAP binding is associated with RNA transcription. Thus, the enhancer regulates accessibility and RNAP binding not only at specific localized sites but across the entire domain. The results support a facilitated tracking model for enhancer activity.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 3. The shared muscle enhancer (ME) directs RNAP binding and RNA transcription across the entire 150 kb locus.

RNAP binding at ‘real’ genes and across the intergenic regions is qualitatively different.

We used naturally occurring single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to investigate allelic differences in binding of RNAP and activation of gene expression in wild-type cells and in cells carrying enhancer deletions or insulator insertion mutations. RNAP binding across the Igf2 and H19 genes is both enhancer-dependent and insulator-sensitive; that is, a functional insulator located between an enhancer and its regulated gene prevents RNAP binding and likewise prevents RNA transcription. Across the intergenic regions, RNAP binding and RNA transcription are similarly enhancer-dependent (see above). However, intergenic RNAP binding and transcription are not insulator-sensitive. The results indicate that insulators do not serve solely as a physical block for RNAP progression, but rather they specifically interfere with certain RNAP states or activities.

The muscle enhancer regulates RNAP binding and RNA transcription but does not establish chromatin structures.

Both RNA transcription and RNAP binding across the Igf2/H19 domain are entirely dependent upon the muscle enhancer. For example, levels of H19 RNA are reduced more than 10,000-fold in muscle cells in which the enhancer has been deleted. To test the dependence of chromatin structure on enhancer activity, we performed ChiP-Seq on wild-type and on enhancer-deletion cell lines using antibodies to the histones H3K4me1, H3K43me3, and H3K36me3. Surprisingly, we saw no changes in the patterns of chromatin modification (Figure 4). Thus, a functional enhancer and active RNA transcription are not important for establishing chromatin structures at this locus.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 4. Chromatin patterns at the Igf2/H19 locus are independent of enhancer activity.

Chromatin was isolated from wild-type and enhancer-deletion muscle cells using antibodies to H3K4me1 and analyzed by DNA sequencing.

Function of the H19 and Igf2 genes in muscle cell growth and differentiation

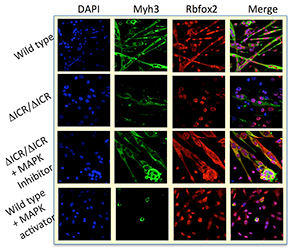

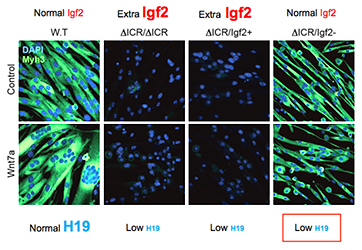

Misexpression of H19 and IGF2 is associated with several developmental diseases (including Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Silver-Russell syndrome) and with several kinds of cancer, especially Wilms' tumor and rhabdosarcoma. In humans, misexpression is most often caused by loss-of-imprinting mutations that result in biallelic expression of IGF2 and loss of expression of H19. We generated and characterized primary myoblast cell lines from mice carrying deletion of the H19 imprinting control region (ICR) that phenocopies the loss-of-imprinting expression phenotypes; that is, ICR–deletion mice make extra Igf2 but no H19. Mice carrying this mutation do not develop rhabdosarcoma but show defects in their ability to respond to and to heal muscle injury. Moreover, primary myoblast lines derived from mutant mice are defective in their ability to differentiate in vitro (Figure 5) (Reference 5).

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 5. Muscle cell–differentiation defects in Igf2/H19 Loss-of-Imprinting mice

Differentiation defects in Loss-of-Imprinting (ΔICR) myoblasts can be rescued by blocking MAP kinase 3 activity. Conversely, artificial activation of the MAPK activity in wild-type cells mimics the genetic defect.

To understand the molecular basis for the differentiation phenotype, we performed RNA sequencing and identified several hundred genes whose expression levels are altered by the ICR deletion. GO (gene ontology) pathway analysis demonstrates that these differentially expressed genes were highly enriched in the MAP kinase signaling pathway. Of special note, expression of the Mapk3 gene is increased almost 10-fold in mutant cell lines.

To determine the significance of the changes in Mapk3, we used drug inhibitors to block MAP kinase activity. In mutant cell lines, we can restore normal differentiation by blocking activation of the MAP kinase target MEK1. Similarly, treatments that activate MAP kinase in wild-type cells can mimic the ICR–deletion phenotype. The results suggest that H19/Igf2 act through MAP kinase to regulate differentiation of myoblast cells.

To distinguish the roles pf Igf2 over-expression and H19 under-expression, we analyzed additional mouse strains that restore H19 via a bacterial artificial chromosome transgene or that restore normal levels of Igf2 expression via a second mutation in the paternal Igf2 gene. Analyses of cell lines from these mice demonstrate that extra Igf2 is the direct cause of failure to differentiate in loss-of-imprinting mutations but that H19 is essential for normal fusion and for muscle hypertrophy in response to Wnt pathways (Figure 6). Further molecular and genetic analyses will uncover the molecular pathways underlying these defects. Furthermore, to understand how the H19 long noncoding RNA can accomplish its functions, we used CRISPR technology to mutagenize conserved domains within the H19 gene, including sites that encode microRNAs and sites that bind to the let7 microRNA.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 6. The long noncoding H19 RNA is required for normal myotube fusion and hypertrophy.

Loss of Imprinting defects at the Igf2/H19 locus result in extra expression of Igf2 and defects in myotube differentiation: Compare W.T (wild type) with DICR/DICR and DICR/Igf2+ cells. Mutation of the paternal Igf2 gene can restore normal Igf2 expression levels and thus restore normal differentiation. (See DICR/Igf2- cells). However, these cells still do not make the H19 long noncoding RNA, do not can fuse efficiently, and do not respond to Wnt7a signaling.

Role of calsequestrin2 in regulating cardiac function

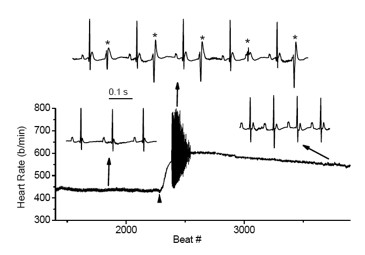

Mutations in the CASQ2 gene, which encodes cardiac calsequestrin (CASQ2), are associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and sudden death. The survival of individuals homozygous for loss-of-function mutations in CASQ2 was surprising, given the central role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction (EC) coupling and the presumed critical roles of CASQ2 in regulating Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) into the cytoplasm. To address this paradox, we generated a mouse model for loss of Casq2 gene activity. Comprehensive analysis of cardiac function and structure yielded several important insights into CASQ2 function. First, CASQ2 is not essential to provide sufficient Ca2+ storage in the SR of the cardiomyocyte. Rather, a compensatory increase in SR volume and surface area in mutant mice appears to maintain normal Ca2+ storage capacity. Second, CASQ2 is not required for the rapid, triggered release of Ca2+ from the SR during cardiomyocyte contraction. Rather, the RyR receptor, an intracellular calcium ion channel, opens appropriately, resulting in normal, rapid flow of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm, thus allowing normal contraction of the cardiomyocyte. Third, CASQ2 is required for normal function of the RyR during cardiomyocyte relaxation. In the absence of CASQ2, significant Ca2+ leaks occur through the RyR and lead to premature contractions and cardiac arrhythmias (Figure 7). Fourth, CASQ2 function is required to maintain normal levels of the SR proteins junctin and triadin. We do not yet understand what role, if any, the compensatory changes in these two SR proteins play in modulating the loss of Casq2 phenotype.

To address these issues and to model cardiac disorders associated with late-onset (not congenital) loss of CASQ2 activity, we established and are analyzing two new mouse models in which changes in Casq2 gene structure are induced by tissue-specific transgenes activated by tamoxifen treatment. In the first model, an invested/null allele is restored to normal function by the addition of the drug. In the past year, we demonstrated the effectiveness of this model and noted that full Casq2 protein levels are restored within one week of treatment. In the second model, a functional gene is ablated by the addition of the drug. The Casq2 gene and mRNAs are deleted from cardiac cells within four days of hormone treatment. Phenotypic analyses shows that restoration of Casq2 in adult animals is sufficient to fully restore cardiac function. Moreover, restoration solely in pacemaking cells is also enough to rescue function, suggesting an important role for reduced heart rate in the CPVT phenotype as well as a new target for therapeutic interventions.

Figure 7. Cardiac arrhythmias in calsequestrin-2–deficient mice phenocopy the human disease.

Premature ventricular complexes (*) are induced by stress in Casq2–deficient but not in wild-type mice.

Publications

- De S, Mitra A, Cheng Y, Pfeifer K, Kassis, JA. Formation of a polycomb-domain in the absence of strong polycomb response elements. PLoS Genet 2016;12:e1006200.

- Ray P, De S, Mitra A, Bezstarosti K, Demmers JA, Pfeifer K, Kassis JA. Compgap contributes to recruitment of Polycomb group proteins in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:3826-3831.

- Eun B, Sampley ML, Good AL, Gebert CM, Pfeifer K. Promoter cross-talk via a shared enhancer explains paternally biased expression of Nctc1 at the Igf2/H19/Nctc1 locus. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:817-826.

- Eun B, Sampley ML, Van Winkle MT, Good AL, Kachman MM, Pfeifer K. The Igf2/H19 muscle enhancer is an active transcriptional complex. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:8126-8134.

- Dey BK, Pfeifer K, Duta, A. The H19 long non-coding RNA gives rise to microRNAs miR-675-3p and -5p to promote skeletal muscle differentiation and regeneration. Genes Dev 2014;28:491-501.

Collaborators

- Leonid V. Chernomordik, PhD, Section on Membrane Biology, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Bjorn Knollmann, MD, PhD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN

- Mark D. Levin, MD, Cardiovascular & Pulmonary Branch, NHLBI, DIR, Bethesda, MD

- Paul Love, MD, PhD, Section on Cellular and Developmental Biology, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Danielle A. Springer, VMD, DCLAM, Animal Program, NHLBI, Bethesda, MD

Contact

For more information, email kpfeifer@helix.nih.gov or visit http://pfeiferlab.nichd.nih.gov.