Cell Cycle Regulation in Oogenesis

- Mary Lilly, PhD, Head, Section on Gamete Development

- Chun-yuan Ting, PhD, Staff Scientist

- Kuikwon Kim, MS, Biologist

- Shu Yang, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Lucia Bettedi, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Yingbiao Zhang Zhang, PhD, Visiting Fellow

Our long-term goal is to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how metabolic signaling pathways influence oocyte growth, development, and quality. Chromosome mis-segregation during female meiosis is the leading cause of miscarriages and birth defects in humans. Recent evidence suggests that many meiotic errors occur downstream of defects in oocyte growth and/or in the hormonal signaling pathways that drive differentiation of the oocyte. Thus, understanding how oocyte development and growth impact meiotic progression is essential to studies in both reproductive biology and medicine. We use the genetically tractable model organism Drosophila melanogaster to examine how meiotic progression is instructed by the developmental and metabolic program of the egg.

In mammals, studies on the early stages of oogenesis face serious technical challenges in that entry into the meiotic cycle, meiotic recombination, and the initiation of the highly conserved prophase I arrest all occur during embryogenesis. By contrast, in Drosophila these critical events of early oogenesis all take place continuously within the adult female. Easy access to the early stages of oogenesis, coupled with available genetic and molecular genetic tools, makes Drosophila an excellent model for studies on the role of metabolism in oocyte development and maintenance.

The GATOR complex: integrating developmental and metabolic signals in oogenesis

The Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (TORC1) regulates cell growth and metabolism in response to many inputs, including amino-acid availability and intracellular energy status. In the presence of sufficient nutrients and appropriate growth signals, the Ragulator and the Rag GTPases (a complex that regulates lysosomal signaling and trafficking) target TORC1 to lysosomal membranes, where TORC1 associates with its activator, the small GTPase Rheb. Once activated, TORC1 is competent to phosphorylate its downstream targets. The Gap activity towards Rags (GATOR) complex is an upstream regulator of TORC1 activity.

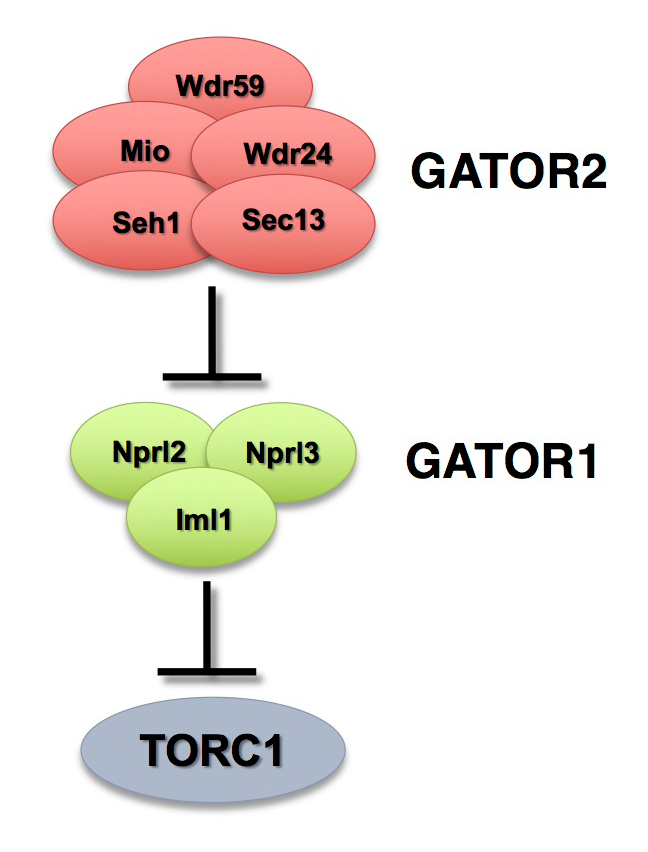

The GATOR complex consists of two subcomplexes (Figure 1). The GATOR1 complex inhibits TORC1 activity in response to amino-acid starvation. GATOR1 is a trimeric protein complex consisting of the proteins Nprl2, Nprl3, and Iml1. Evidence from yeast and mammals indicates that the components of the GATOR1 complex function as GTPase–activating proteins (GAP) that inhibit TORC1 activity by inactivating the Rag GTPases. Notably, Nprl2 and Iml1 are tumor-suppressor genes, while mutations in Iml1, known as DEPDC5 in mammals, are a leading cause of hereditary epilepsy.

The GATOR2 complex comprises five proteins: Seh1, Sec13, Mio, Wdr24, and Wdr59. Our work, as well as that of others, found that the GATOR2 complex activates TORC1 by opposing the TORC1–inhibitory activity of GATOR1. Intriguingly, computational analysis indicates that Mio and Seh1, as well as several other members of the GATOR2 complex, have structural features consistent with coatomer proteins and membrane-tethering complexes. In line with the structural similarity to proteins that influence membrane curvature, we showed that three components of the GATOR2 complex, Mio, Seh1, and Wdr24, localize to the outer surface of lysosomes, the site of TORC1 regulation. However, how GATOR2 inhibits GATOR1 activity, thus allowing for the robust activation of TORC1, remains unknown. Additionally, the role of the GATOR1 and GATOR2 complexes in both the development and physiology of multicellular animals remains poorly defined. Over the past year, we used molecular, genetic, and cell-biological approaches to define the role of the GATOR complex in the regulation of meiotic progression and genomic stability during oogenesis. Moreover, we used oogenesis as a model system to define a novel mechanism of TORC1 inhibition in response to both amino acid and growth factor restriction.

Figure 1. The GATOR complex regulates TORC1 activity.

The GATOR2 complex opposes the activity of the TORC1 inhibitor GATOR1.

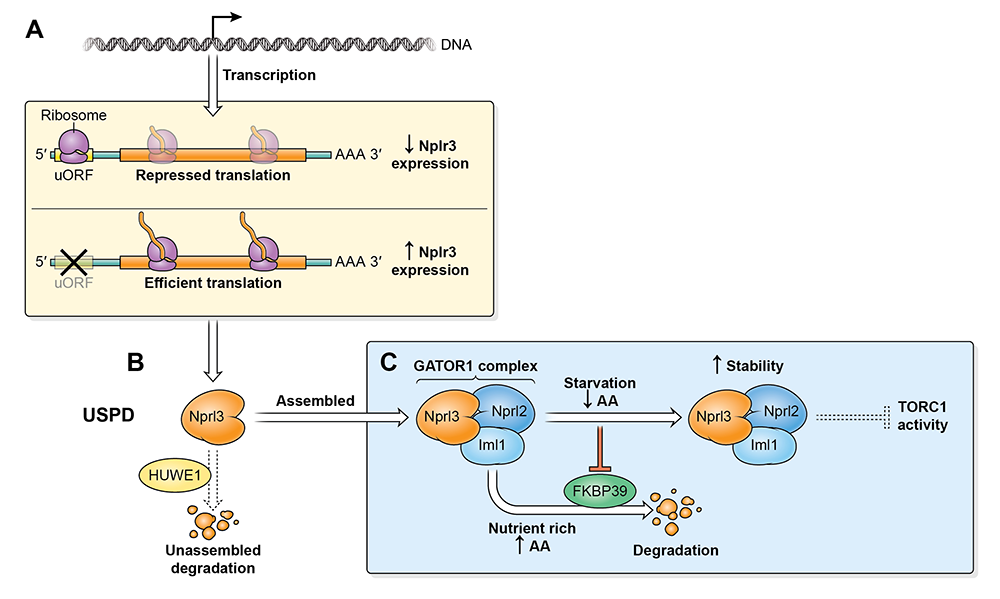

Multiple independent pathways converge on Nprl3 to regulate TORC1 activity in Drosophila.

In collaboration with the laboratory of Youheng Wei, we characterized several pathways that regulate the expression of the GATOR1 component Nprl3 in Drosophila (Figure 2). We determined that the stability of Nprl3 is impacted by the Unassembled Soluble Complex Proteins Degradation (USPD) pathway. In addition, we found that FK506 binding protein 39 (FKBP39)–dependent proteolytic destruction maintains Nprl3 at low levels in nutrient-replete conditions. Nutrient starvation abrogates the degradation of the Nprl3 protein and rapidly promotes Nprl3 accumulation. Consistent with a role in promoting the stability of a TORC1 inhibitor, mutations in fkbp39 reduced TORC1 activity and increased autophagy. We also demonstrated that the 5′UTR of nprl3 transcripts contain a functional upstream open-reading frame (uORF) that inhibits main ORF translation. In summary, our work has uncovered novel mechanisms of Nprl3 regulation and identifies an important role for Drosophila FKBP39 in the control of cellular metabolism and growth.

Figure 2. Multiple pathways regulate the levels of the TORC1 inhibitor Nprl3.

A. The nprl3 mRNA contains a functional uORF that reduces Nprl3 translation.

B. Nprl3 forms the trimeric GATOR1 complex with the proteins Nprl2 and Iml1. When not assembled into the GATOR1 complex, Nprl3 is degraded via a HUWEI–dependent pathway.

C. In nutrient-replete conditions, FKBP39 associates with Nprl3 and promotes its degradation. Upon amino acid starvation, the FKBP39–dependent destruction of Nprl3 is blocked, and the increased levels of GATOR1 result in reduced TORC1 activity.

A unified model of TORC1 regulation: the Rag GTPase regulates the dynamic behavior of TSC downstream of both amino-acid and growth-factor restriction.

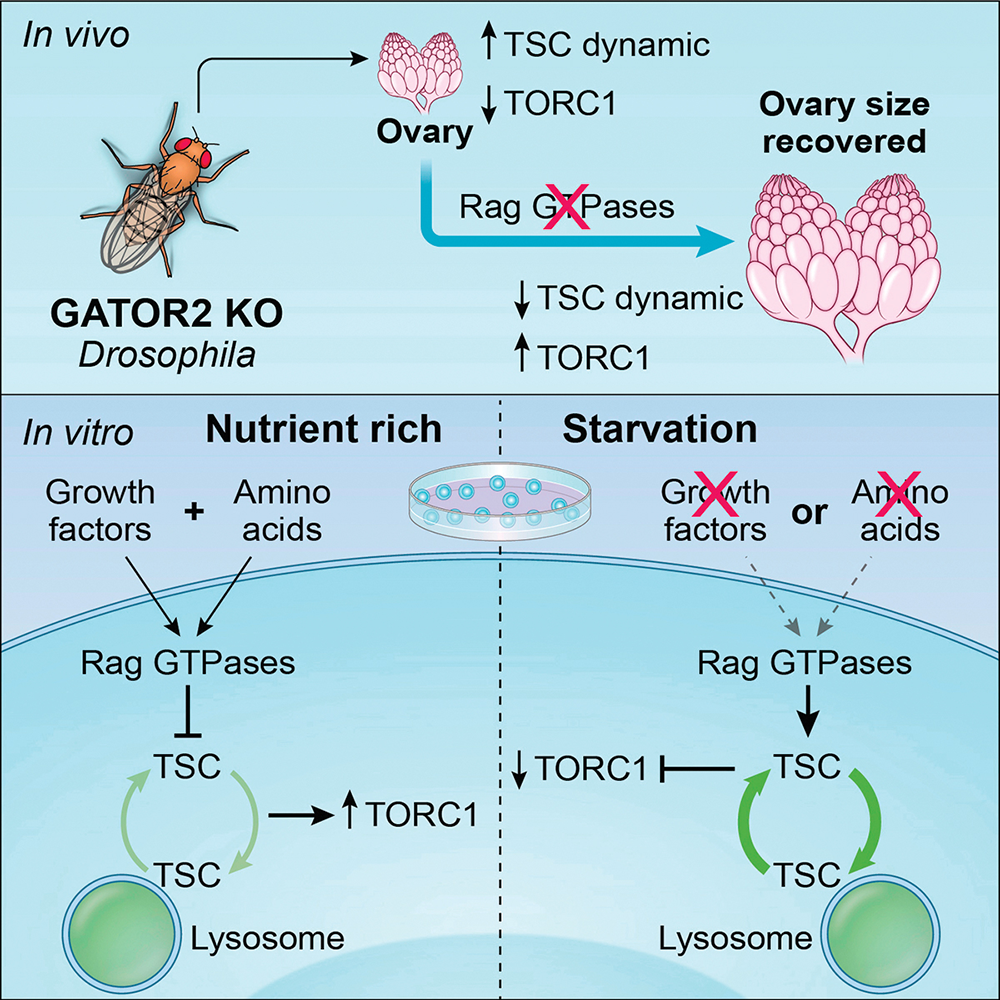

The dysregulation of the metabolic regulator TORC1 contributes to a wide array of human pathologies. Tuberous sclerosis is a rare multi-organ genetic disorder affecting 1 in 6,000 newborns a year. Mutations in components of the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) result in the hyperactivation of TORC1, causing the growth of benign tumors in many parts of the body. Although the importance of the TSC in cell metabolism is well established, a detailed understanding of its regulation has remained elusive. We used Drosophila melanogaster and tissue-culture cells to demonstrate that the GATOR2 complex is a novel regulator of TSC. The GATOR1 subcomplex inhibits the activity of TORC1 by preventing the recruitment of the complex to lysosomes, where it encounters its activator Rheb. Specifically, GATOR1 regulates TORC1 localization by serving as a GTPase–activating protein for RagA/B; in their GTP–bound status, RagA/B recruit TORC1 to lysosomes. The GATOR2 complex opposes the activity of GATOR1.

Using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), we determined that knocking out WDR24, one of the subunits of the GATOR2 complex, resulted in the rapid recruitment of the TSC subunits TSC2 and TSC1 to lysosomes in both Hela cells and in the Drosophila ovary. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the GATOR2 complex regulates TSC2 dynamics by controlling the guanine nucleotide–binding status of the RagA or RagC small GTPases. Specifically, GDP–bound RagA and GTP–bound RagC promote the dynamic recruitment of TSC2 to lysosomes. Moreover, by using a photoconvertible protein–tagged TSC2, we determined that the rapid association of TSC2 to lysosomes is accompanied by its rapid dissociation in wdr24–/– cells. Taking together, we provided both in vitro and in vivo evidence to support the model that the GATOR complex regulates the dynamic cycling of the TSC between lysosomes and the cytoplasm (Figure 3).

Currently, there are two working models for the role of TSC in the inhibition of TORC1 activity. The first model posits that TSC lies exclusively downstream of the PI3K-AKT growth-factor signaling pathway, while the second model proposes that TSC is a critical downstream effector of both the growth-factor signaling and amino acid–sensing pathways. Our findings on the function of the GATOR2 complex are consistent with the second model, which implicate different nucleotide states of the Rag GTPase in the recruitment of TORC1 versus TSC to lysosomes in response to amino-acid starvation. Moreover, we determined that the Rag GTPase, which was previously thought to exclusively function in amino-acid sensing, regulates the recruitment of TSC to lysosomes in response to growth-factor restriction. Thus, our data support a model in which both the amino acid–sensing pathway and growth factor–signaling pathway converge on the Rag GTPase to recruit TSC to lysosomes in response to inhibitory signals. Notably, we found that, both in HeLa cells and Drosophila, the Rag GTPase promotes the rapid exchange of TSC between the lysosome and cytosol in response to negative inputs. Moreover, the rate of exchange mirrors TSC function, with depletions of the Rag GTPase blocking TSC lysosomal mobility and rescuing TORC1 activity. Demonstrating further integration of the amino acid–sensing and growth factor–signaling pathways, we showed that the GATOR2 complex acts upstream of the Rag GTPase to promote both the activating phosphorylation of AKT and the AKT–dependent inhibitory phosphorylation of TSC2.

Figure 3. Integrated model of TORC1 regulation

The Rag GTPase integrates information from the amino-acid and growth-factor signaling pathways to control the activation of the TORC1 inhibitor TSC by regulating its lysosomal-cytosolic exchange rate.

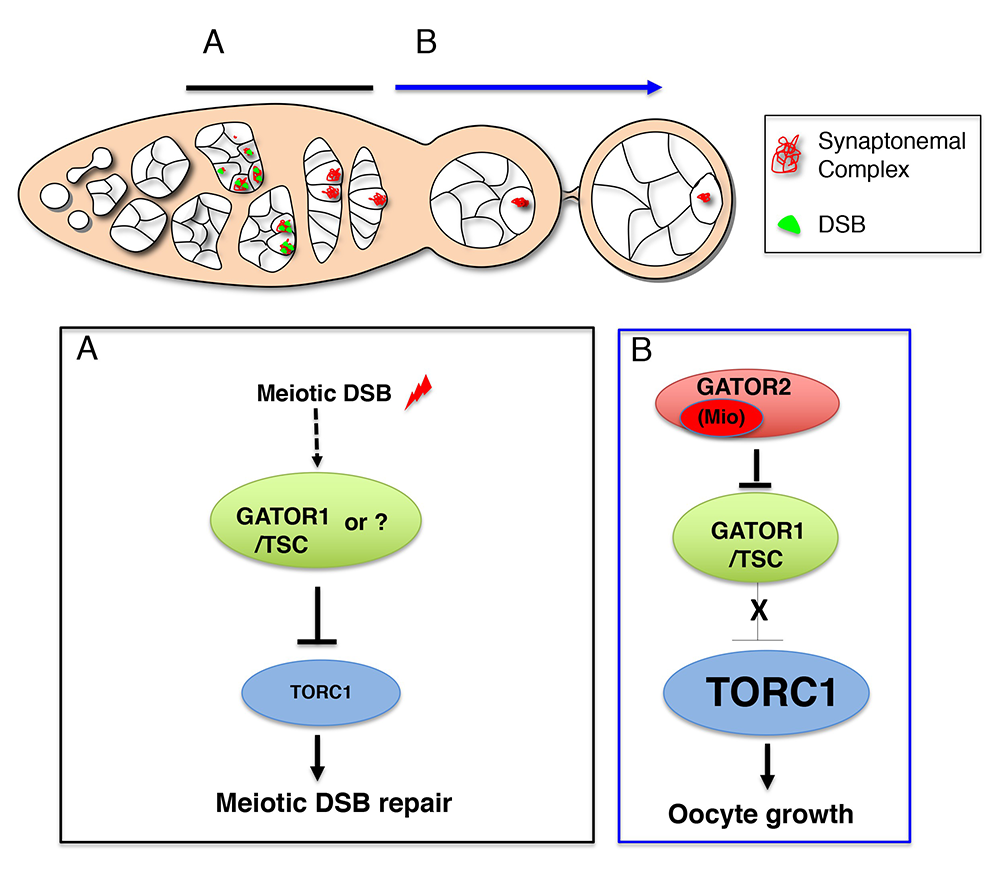

The GATOR complex regulates an essential response to meiotic double-stranded breaks.

The TORC1 inhibitor GATOR1 controls meiotic entry and early meiotic events in yeast. However, how metabolic pathways influence meiotic progression in metazoans remains poorly understood. During the past year, we expanded our examination into how the TORC1 regulators GATOR1 and GATOR2 mediate a response to meiotic DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) during Drosophila oogenesis. The initiation of homologous recombination through the programmed generation of DNA DSBs is a universal feature of meiosis. DSBs represent a dangerous form of DNA damage, which can result in dramatic and permanent changes to the germline genome. To minimize their destructive potential, the generation and repair of meiotic DSBs is tightly controlled in space and time. We showed that meiotic DSBs promote the GATOR1–dependent down-regulation of TORC1 activity. Consistent with this observation, we found that mutants in genes such as the Rad51 homolog spnA, which retain meiotic DSBs into late stages of oogenesis, exhibit a profound reduction in TORC1 activity in the female germline, data that suggest that low TORC1 activity may be important for the efficient repair of meiotic DSB. In line with this hypothesis, we determined that GATOR1–mutant ovaries, which have high levels of TORC1 activity, exhibit many phenotypes consistent with the mis-regulation of meiotic DSBs, including an increase in the steady-state number of meiotic DSBs, the retention of meiotic DSBs into later stages of oogenesis, and the hyperactivation of p53, a transcription factor that mediates a highly conserved response to genotoxic stress. Importantly, RNAi depletions of Tsc1 phenocopied the GATOR1 ovarian defects. TSC1 is a component of the potent TORC1 inhibitor Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), confirming that the mis-regulation of meiotic DSBs observed in GATOR1–mutant oocytes is attributable to high TORC1 activity rather than to a TORC1–independent function of the GATOR1 complex. Further genetic analysis revealed that many of the phenotypes associated with high TORC1 activity observed in GATOR1–mutant ovaries are the result of the hyperactivation of the downstream TORC1 target S6K. We also demonstrated that GATOR1 impacts the repair, rather than the generation, of meiotic DSBs. Our data are particularly intriguing in light of similar meiotic defects observed in npr3 mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The results raise the possibility that GATOR1–mediated downregulation of TORC1 activity may be a common feature of the early meiotic cycle in many eukaryotes.

Genotoxic stress has been implicated in the deregulation of retrotransposon expression in several organisms, including Drosophila. In line with these studies, we found that, in GATOR1 mutants, the double-stranded breaks that initiate meiotic recombination trigger the deregulation of retrotransposon expression. Similarly, it was previously shown that p53–mutant females de-repress retrotransposon expression during oogenesis, but, as observed in GATOR1 mutants, primarily in the presence of meiotic DSBs. Through epistasis analysis, we determined that p53 and GATOR1 act through independent pathways to repress retrotransposon expression in the female germline. Surprisingly, we found that depletions of the TORC1 inhibitor TSC in the female germline resulted in little or no increase in retrotransposon expression. The data raise the interesting possibility that GATOR1 regulates retrotransposon expression independently of TORC1 activity. Notably, GATOR1 components, but not TSC components, were recently identified in a high-throughput screen for genes that suppress LINE1 (Long Interspersed Element-1) expression in mammalian tissue-culture cells. Taken together, our data indicate that the GATOR1 complex opposes retrotransposon expression during meiosis in a pathway that functions in parallel to p53 in the female germline of Drosophila.

Figure 4. Working model for the role of the GATOR complex in the response to meiotic DSBs

A. After ovarian cysts enter meiosis, meiotic DSBs function to activate and/or maintain a GATOR1/TSC–dependent pathway to ensure low TORC1 activity in early prophase of meiosis I. Low TORC1 activity promotes the timely repair of meiotic DSBs. Currently, whether meiotic DSBs directly activate the GATOR1/TSC pathway or an alternative pathway that works in concert with, or in parallel to, GATOR1/TSC is not known.

B. Subsequently, the GATOR2 component Mio is required to attenuate the activity of the GATOR1/TSC pathway, thus allowing for increased TORC1 activity and the growth and development of the oocyte in later stages of oogenesis.

Publications

- Zhou Y, Guo J, Wang X, Cheng Y, Guan J, Barman P, Sun MA, Fu Y, Wei W, Feng C, Lilly MA, Wei Y. FKBP39 controls nutrient dependent Nprl3 expression and TORC1 activity in Drosophila. Cell Death Dis 2021;12(6):571.

- Yang S, Zhang Y, Ting C-Y, Bettedi L, Kim K, Ghaniam E, Lilly MA. The Rag GTPase regulates the dynamic behavior of TSC downstream of both amino acid and growth factor restriction. Dev Cell 2020;55(3):272–288.

- Wei Y, Kim K, Bettedi L, Ting CY, Zhang Y, Cai J, Lilly MA. The GATOR complex regulates an essential response to meiotic double-stranded breaks in Drosophila. eLife 2019;8:pii e42149.

- Xi J, Cai J, Cheng Y, Fu Y, Wei W, Zhang Z, Shuang Z, Hao Y, Lilly MA, Wei Y. The TORC1 inhibitor Nprl2 protects age-related digestive function in Drosophila. Aging 2019;11(21):9811–9828.

- Rotelli M, Policastro R, Bolling A, Killion A, Weinbeerg A, Dixon M, Zenter D, Walczak C, Lilly M, Calvi B. A Cyclin A-Myb-Aurora B network regulates the choice between mitotic cycles and polyploid endoreplication cycles. PLoS Genet 2019;15(7):e1008253.

Collaborators

- Brian Calvi, PhD, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

- Ryan Dale, PhD, Bioinformatics and Scientific Programming Core, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Thomas Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis, PhD, Functional Transciptomics Section, NCI, Frederick, MD

- Mark Nellist, PhD, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- Youheng Wei, PhD, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China

Contact

For more information, email mlilly@helix.nih.gov or visit https://irp.nih.gov/pi/mary-lilly.