Molecular Genetics of Endocrine Tumors and Related Disorders

- Constantine Stratakis, MD, D(med)Sci, Head, Section on Endocrinology and Genetics

- Fabio Faucz, PhD, Staff Scientist

- Edra London, PhD, Staff Scientist

- Elena Belyavskaya, MD, PhD, Physician Assistant

- Charalampos Lyssikatos, MD, Research Associate

- Antonios Voutetakis, MD, PhD, Research Scholar Associate

- Annabel Berthon, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Ludivine Drougat, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Laura Hernández-Ramírez, MD, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Paraskevi Salpea, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Nickolas Settas, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Giampaolo Trivellin, PhD, Visiting Fellow

- Mari Suzuki, MD, Clinical Associate (Internal Medicine Endocrinology Fellow)

- Christina Tatsi, MD, Clinical Associate (Pediatric Endocrinology Fellow)

- Mihail Zilbermint, MD, Clinician Associate (Johns Hopkins University)

- Madelauz (Lucy) Sierra, MSc, Research Assistant

- Amit Tirosh, MD, Contractor — Clinical Scientist (Israel)

- Nuria Valdés Gallego, MD, Clinical Researcher on Sabbatical (Spain)

- Jennifer Gourgaris, MD, Guest Researcher (Georgetown University Faculty)

- Annita Boulouta, MD, Visiting Medical Trainee

- Sara Piccini, MD, Visiting Medical Trainee

- Carolina Saldarriagga, MD, Visiting Medical Trainee

- Minghi Hu, MD, Visiting Professor

- Atila Duque Rossi, BS, MS, Visiting Research Student

- Michelle Bloyd, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Niko Darby, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Rachel Wurth, MS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Jancarlos Camacho, BS, Summer Student

In the project that was started in the late 1990s, our approach has been to study patients with rare endocrine conditions, mostly inherited, identify the causative genes, and then study the signaling pathways involved in the hope of translating the derived knowledge into new therapies for such patients. The derived knowledge could also be generalized to conditions that are not necessarily inherited, e.g., to more common tumors and diseases caused by defects in these molecular pathways. Our first studies led to the identification of the main regulator of the cAMP signaling pathway, the regulatory subunit type 1A (R1a) of protein kinase A (PKA, encoded by the PRKAR1A gene on chromosome 17q22-24), as responsible for primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) and the Carney complex, a multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN), whose main endocrine manifestation is PPNAD. We then focused on clinically delineating the various types of primary bilateral adrenal hyperplasias (BAHs). We described isolated micronodular adrenocortical disease (iMAD), a disorder likely to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and unrelated to the Carney complex or to other MENs. The identification of PRKAR1A mutations in PPNAD led to the recognition that non-pigmented forms of BAH exist, and a new nomenclature was proposed, which we first suggested in 2008 and is since used worldwide.

In the project that was started in the late 1990s, our approach has been to study patients with rare endocrine conditions, mostly inherited, identify the causative genes, and then study the signaling pathways involved in the hope of translating the derived knowledge into new therapies for such patients. The derived knowledge could also be generalized to conditions that are not necessarily inherited, e.g., to more common tumors and diseases caused by defects in these molecular pathways. Our first studies led to the identification of the main regulator of the cAMP signaling pathway, the regulatory subunit type 1A (R1a) of protein kinase A (PKA, encoded by the PRKAR1A gene on chromosome 17q22-24), as responsible for primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) and the Carney complex, a multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN), whose main endocrine manifestation is PPNAD. We then focused on clinically delineating the various types of primary bilateral adrenal hyperplasias (BAHs). We described isolated micronodular adrenocortical disease (iMAD), a disorder likely to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and unrelated to the Carney complex or to other MENs. The identification of PRKAR1A mutations in PPNAD led to the recognition that non-pigmented forms of BAH exist, and a new nomenclature was proposed, which we first suggested in 2008 and is since used worldwide.

In 2006, a genome-wide association (GWA) study led to the identification of mutations in the phosphodiesterases (PDE) PDE11A, a dual-specificity PDE, and in PDE8B, a cAMP–specific PDE (encoded by the PDE11A and PDE8B genes, respectively) in iMAD. Following the establishment of cAMP/PKA involvement in PPNAD and iMAD, we and others discovered that elevated cAMP levels and/or PKA activity and abnormal PDE activity may be found in most benign adrenal tumors (ADTs), including the common adrenocortical adenoma (ADA). We then found PDE11A and PDE8B mutations or functional variants thereof in adrenocortical cancer (ACA) and in other forms of adrenal hyperplasia such as massive macronodular adrenocortical disease (MMAD), also known as ACTH–independent adrenocortical hyperplasia (MMAD/AIMAH). Germline PDE11A sequence variants may also predispose to testicular cancer (testicular germ-cell tumors or TGCTs) and prostate cancer, indicating a wider role of this tumor-formation pathway in cAMP–responsive, steroidogenic, or related tissues. Ongoing work with collaborating NCI laboratories aims to clarify the role of PDE in the predisposition to these tumors. However, it is clear from these data that there is significant pleiotropy of PDE11A and PDE8B defects. The histomorphological studies that we performed on human adrenocortical tissues from patients with these mutations showed that iMAD is highly heterogeneous and thus likely to be caused by defects in various genes of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway or its regulators and/or downstream effectors.

Similarly, the G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR)–linked MMAD/AIMAH disease includes a range of adrenal phenotypes, from those very similar to iMAD to primary bimorphic adrenocortical disease (PBAD) and McCune-Albright syndrome, which is caused by somatic mutations in the GNAS gene (encoding the G protein–stimulatory subunit alpha [Gsα]). Although a few of the patients with MMAD/AIMAH have germline PDE11A, PDE8B, or somatic GNAS mutations, others have mutations in the genes encoding germline fumarate hydratase (FH), menin (MEN1), or adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), pointing to the range of possible pathways that may be involved. Particularly interesting among these are FH mutations that are associated with mitochondrial oxidation defects linked to adrenomedullary tumors, which led us to investigate a disorder known as the Carney Triad. The Carney Triad is the only known disease that, among its clinical manifestations, has both adrenocortical (ADA, MMAD/AIMAH) and medullary tumors (pheochromocytomas [PHEOs] and paragangliomas [PGLs]), in addition to hamartomatous lesions in various organs (pulmonary chondromas and pigmented and other skin lesions) and a predisposition to gastrointestinal stromal tumors or sarcomas (GISTs). A subgroup of patients with PHEOs, PGLs, and GISTs were found to harbor mutations in succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunits B, C, and D (encoded by the SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD genes, respectively); the patients also rarely have adrenocortical lesions, ADAs, and/or hyperplasia, and their disease is known as the dyad or syndrome of PGLs and GISTs and is now widely known as the Carney-Stratakis syndrome (CSS).

In 2013, MMAD/AIMAH was renamed primary macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia (PMAH) after it was discovered that it depends on adrenoglandular ACTH production, at least occasionally. As part of this work, a new gene (ARMC5) was identified that, when mutated, causes more than a third of the known PMAH cases. The function of the gene is unknown, and we thus embarked on a project to characterize it further, including studying mouse, fruit fly, and fish models. The ARMC5 gene has a beta-catenin–like motif.

Although PPNAD appears to be less heterogeneous and is mostly caused by PRKAR1A mutations, up to one third of patients with the classic features of PPNAD do not have PRKAR1A mutations, deletions, or 17q22–24 copy-number variant (CNV) abnormalities. A subset of these patients may have defects in other molecules of the PKA holoenzyme, and studying them is important for understanding how PKA works as well as the tissue specificity of each defect. For patients with disorders that are yet to be elucidated on a molecular level, we continue to delineate the phenotypes and identify the responsible genetic defects through a combination of genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Recently, we identified genes encoding two other subunits of PKA as involved in endocrine tumors: PRKACA in BAH and PRKACB in a form of the Carney complex that is not associated with PRKAR1A mutations. Our laboratory is now investigating the two genes.

Animal model studies are essential for investigating and confirming each of the identified new genes in disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, such studies provide insight into function that can be tested quickly in human samples for confirmation of its relevance to human disease. One excellent example of such a bench-to-bedside (and back) process was our recent identification, from a variety of animal experiments, of Wingless/int (Wnt) signaling as one of the pathways interacting with cAMP/PKA in the adrenal cortex. We continue to investigate the pathways involved in early events in tumor formation in the adrenal cortex and/or the tissues affected by germline or somatic defects of the cAMP/PKA and related endocrine signaling defects, employing animal models and transcriptomic and systems-biology analyses. Understanding the role of the other PKA subunits in this process is essential. An example of the combined use of whole genomic tools, transcriptomic analysis, and mouse and zebrafish models to investigate the function of a gene or a pathway is the ongoing work on the Carney Triad.

We continue to accrue patients under several clinical protocols, identify unique patients and families with rare phenotypes, and/or explore (mostly on a collaborative basis) various aspects of endocrine and related diseases. Paramount to these investigations is the availability of modern genetic tools such as copy-number variation (CNV) analysis, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and DNA sequencing (DNA-Seq). As part of the clinical protocols, much clinical research consists mostly of observations of new associations, description of novel applications or modifications, and improvements in older diagnostic methods, tests, or imaging tools, a particularly fruitful area of research, especially for our clinical fellows, who matriculate at our laboratory during their two-year research time. The approach also leads to important new discoveries, which may steer us into new directions.

One such discovery was our recent identification of the defect that explains the vast majority of cases of early pediatric overgrowth or gigantism. What regulates growth, puberty, and appetite in children and adults is poorly understood. We identified the gene GPR101, encoding a G protein–coupled receptor, that was overexpressed in patients with elevated growth hormone (GH). Patients with GPR101 defects have a condition that we called X-LAG, for X-linked acrogigantism, which is caused by Xq26.3 genomic duplication and is characterized by early-onset gigantism resulting from excess GPR101 function and consequent elevation of GH. Another recent discovery was the identification of SGPL1 (sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase 1) deficiency in patients with primary adrenocortical insufficiency.

As the era of rare diseases gene discovery comes to an end, with more than half of them now molecularly elucidated, and in excess of 30 genetic associations studied by the Section’s researchers over the last 25 years, the Section follows the shift that was first proposed in 2016: the clinical protocols that focused on Carney complex (1995–2020), adrenal hyperplasia (2000–2020), and other adrenal disorders were closed in 2020, as their main goals were accomplished (i.e., elucidation of the main genetic causes leading to these tumors). We replaced these studies with disease-specific, new molecular treatment trials (e.g., Pegvisomant® treatment of children with gigantism, supported by Pfizer, Inc.) and research on common disorders that relate to the rare diseases and their molecular pathways that we have been investigating (e.g., clinical and molecular characteristics of primary aldosteronism in Black individuals, a collaborative program with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and others).

In the laboratory, too, our emphasis is on the identification of molecular targets that may lead to clinical trials that we will implement at the NIH CRC. We have already identified compounds in both our PRKACA and GPR101 screening efforts. We are now characterizing the compounds in the laboratory and, soon, in animal models. The work would not have been done without access to NIH’s Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and its Chemical Genomics Center (now Early Translation Branch or ETB), as well as several international collaborators.

Carney complex (CNC) genetics

We collected families with CNC and related syndromes from several collaborating institutions worldwide. Through genetic linkage analysis, we identified loci harboring genes for CNC on chromosomes 2 (2p16) and 17 (17q22–24). The PRKAR1A gene on 17q22–24, the gene responsible for CNC in most cases of the disease, appears to undergo loss of heterozygosity in at least some CNC tumors. PRKAR1A is also the main regulatory subunit (subunit type 1-alpha) of PKA, a central signaling pathway for many cellular functions and hormonal responses. We increased the number of CNC patients in genotype-phenotype correlation studies, which are expected to provide insight into the complex biochemical and molecular pathways regulated by PRKAR1A and PKA. We expect to identify new genes by ongoing genome-wide searches for patients and families who do not carry PRKAR1A mutations.

Mutations in PRKAR1A and protein kinase A activity in other diseases

We are investigating the functional and genetic consequences of PRKAR1A mutations in cell lines from a variety of tumors. We measure both cAMP and PKA activity in the cell lines, along with the expression of the other subunits of the PKA tetramer. We work to identify PRKAR1A–interacting mitogenic and other growth-signaling pathways in cell lines expressing PRKAR1A constructs and/or mutations. Several genes that regulate PKA function and increase cAMP–dependent proliferation and related signals may be altered in the process of endocrine tumorigenesis initiated by a mutant PRKAR1A, a gene with important functions in the cell cycle and in chromosomal stability.

In 2018, we were successful in obtaining funded through a Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Award on the “Genetics of human susceptibility to infections and/or complications of Zika virus: variants of the cyclic AMP-dependent PKA pathway.” The resulting publication [Rossi AD et al., J Intern Med 2019;285:215] described an association between Zika virus disease burden and certain variants of genes involved in the cAMP signaling pathway.

Prkar1a+/– and related animal models

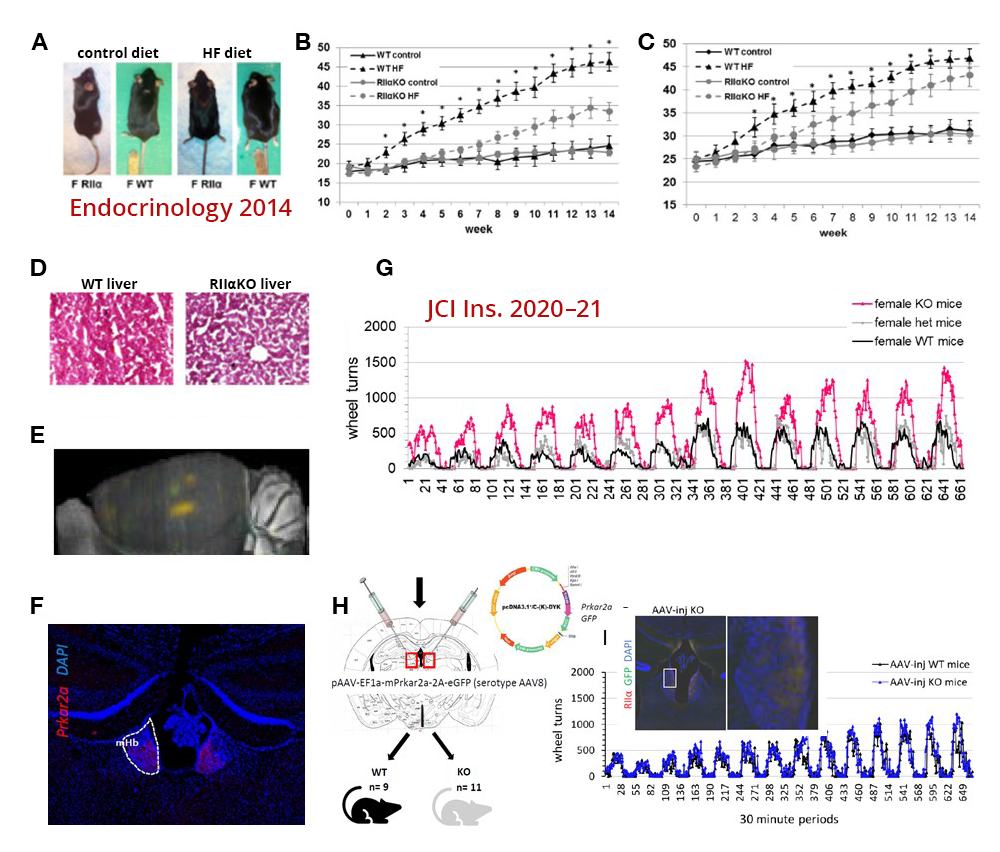

Several years ago, we developed a Prkar1a knockout mouse floxed by a lox-P system for the purpose of generating, first, a novel Prkar1a+/– and, second, knockouts of the Prkar1a gene in a tissue-specific manner after crossing the new mouse model with mice expressing the cre protein in the adrenal cortex, anterior lobe of the pituitary, and thyroid gland. The heterozygote mouse develops several tumors reminiscent of the equivalent human disease. We have now developed new crosses that demonstrate protein kinase A subunit involvement in additional phenotypes. An example of the ongoing work using PKA–subunit animal models is the work on the Prkar2a mouse model (Figure 1). Ongoing work with several animal crosses is investigating various aspects of PKA subunit functions and the possible involvement of cAMP–pathway perturbations in several pathophysiologic and/or disease-related states.

Figure 1.

A. After a high-fat diet (HFD), Prkar2a knockout (KO) mice were leaner than wild-type (WT).

B, C & D. Female and male KO mice remained leaner as they aged and did not develop a fatty liver after a HFD.

E & F. Prkar2a expression was mapped to the medial habenula (MHb) and, in part, the leaner phenotype was the result of reduced HFD intake.

G. Female (shown) and male KO mice (not shown) run more than twice as much as WT during home cage running wheel access.

H & I. Direct injection of Prkar2a into the MHb reduced voluntary running* to the levels of WT and restored sucrose preference.

*Voluntary running activity was graphed in bins of 30 minutes over a two-week period.

The Prkar2a–/– mouse is involved in motivation to exercise and has preference for certain foods.

The habenula (Hb) is a bilateral, evolutionarily conserved epithalamic structure connecting forebrain and midbrain structures, which has gained attention for its roles in depression, addiction, rewards processing, and motivation. Of its two major subdivisions, the medial Hb (MHb) and lateral Hb (LHb), MHb circuitry and function are poorly understood compared with those of the LHb. Prkar2a encodes the cAMP–dependent protein kinase (PKA) regulatory subunit IIa (RIIa), a component of the PKA holoenzyme, which is at the center of one of the major cell-signaling pathways conserved across systems and species. Type 2 regulatory subunits (RIIα, RIIβ) determine the subcellular localization of PKA, and, unlike other PKA subunits, Prkar2a shows minimal brain expression except in the MHb. We previously showed that RIIα-knockout (RIIα-KO) mice resist diet-induced obesity. More recently, we reported that RIIα-KO mice consume less palatable, ‘rewarding’ foods and are more motivated for voluntary exercise. Prkar2a deficiency led to decreased habenular PKA enzymatic activity and impaired dendritic localization of PKA catalytic subunits in MHb neurons. Re-expression of Prkar2a in the Hb rescued this phenotype, confirming differential roles for Prkar2a in regulating the drives for palatable foods and voluntary exercise. Our findings show that, in the MHb, decreased PKA signaling and dendritic PKA activity reduce motivation for palatable foods, while enhancing the motivation for exercise, a desirable combination of behaviors (Figure 1).

Genes encoding phosphodiesterase (PDE) in endocrine and other tumors

In patients who do not exhibit CNC or have PRKAR1A mutations but present with bilateral adrenal tumors similar to those in CNC, we found inactivating mutations of the PDE11A gene, which encodes phosphodiesterase-11A (PDE11A), an enzyme that regulates PKA in the normal physiologic state. Phosphodiesterase 11A is a member of a 22 gene–encoded family of proteins that break down cyclic nucleotides that control PKA. PDE11A appears to act as a tumor suppressor such that tumors develop when its action is abolished. In what proved to be the first cases in which mutated PDE was observed in a genetic disorder predisposing to tumors, we found pediatric and adult patients with bilateral adrenal tumors. Recent data indicate that PDE11A–sequence polymorphisms may be present in the general population. The finding that genetic alterations of such a major biochemical pathway may be associated with tumors in humans raises the reasonable hope that drugs that modify PKA and/or PDE activity may eventually be developed to treat both CNC patients and those with other, non-genetic, adrenal tumors, and perhaps other endocrine tumors. After the identification of a patient with a PDE8B mutation and Cushing’s syndrome, additional evidence emerged that yet another cAMP–specific PDE is involved in endocrine conditions. We also studied both Pde11a and Pde8b animal models.

Genetic investigations into other adrenocortical diseases and related tumors

Through collaborations, we: (1) apply general and pathway-specific microarrays to a variety of adrenocortical tumors, including single adenomas and MMAD, to identify genes with important functions in adrenal oncogenetics; (2) examine candidate genes for their roles in adrenocortical tumors and development; and (3) identify additional genes that play a role in inherited pituitary, adrenocortical, and related diseases.

This past year, in collaboration with a group in France, we investigated the genetic defects in GIP–dependent Cushing’s syndrome, which is caused by ectopic expression of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) in cortisol-producing adrenal adenomas or in bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasias. We performed molecular analyses on the adrenocortical adenomas and bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasias obtained from 14 patients with GIP–dependent adrenal Cushing’s syndrome and one patient with GIP–dependent aldosteronism. GIPR expression in all adenoma and hyperplasia samples occurred through transcriptional activation of a single allele of the GIPR gene. While no abnormality was detected in proximal GIPR promoter methylation, we identified somatic duplications in chromosome region 19q13.32, which contains the GIPR locus, in the adrenocortical lesions derived from three patients. In two adenoma samples, the duplicated 19q13.32 region was rearranged with other chromosome regions, whereas a single tissue sample with hyperplasia had a 19q duplication only. Our French collaborators showed that juxtaposition with cis-acting regulatory sequences, such as glucocorticoid-response elements, in the newly identified genomic environment drives abnormal expression of the translocated GIPR allele in adenoma cells.

We continue to work on identifying new genetic defects in other forms of adrenal tumors and/or hyperplasias. We have now identified variants in PRKAR1B and PRKACB predisposing to adrenal tumors, in addition to PRKACA, ARMC5, and of course PRKAR1A.

Genetic investigations into pituitary tumors, X-LAG, other endocrine neoplasias, and related syndromes

In collaboration with several other investigators at the NIH and elsewhere, we are investigating the genetics of CNC– and adrenal-related endocrine tumors, including childhood pituitary tumors, related or unrelated to PRKAR1A mutations. As part of this work, we identified novel genetic abnormalities.

We identified the gene GPR101, which encodes an orphan G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) and is overexpressed in patients with elevated growth hormone (GH) or gigantism. Patients with GPR101 defects have a condition that we called X-LAG, for X-linked acrogigantism, which is caused by Xq26.3 genomic duplication and characterized by early-onset gigantism resulting from excessive GPR101 function and consequent GH excess. To find additional patients with this disorder, we collaborated with a group in Belgium, but all the molecular work for gene identification was carried out here at the NIH. We found that the gene is expressed in areas of the brain that regulate growth, and we are actively investigating small-molecule compounds that may bind to GPR101 (unpublished).

In addition, we studied patients with pediatric Cushing disease (CD), which results from corticotropin (ACTH)–secreting pituitary tumors, as part of our studies on Cushing’s syndrome. Almost everything known today in the literature about pediatric CD, from its molecular investigations to its diagnosis and treatment, is derived from work that was done at the NIH. This laboratory is currently intensely involved in identifying genetic defects that predispose to pediatric CD. Last year, we reported CABLES1 (encoding a cyclin-dependent kinase-binding protein) and USP8 (encoding ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 8) mutations in patients with CD (CABLES1) and/or their tumors (USP8).

Genetic investigations into the Carney Triad, other endocrine neoplasias, and related syndromes and into hereditary paragangliomas and related conditions

As part of a collaboration with other investigators at the NIH and elsewhere (including an international consortium organized by our laboratory), we are studying the genetics of the Carney Triad, a rare syndrome that predisposes to adrenal and other tumors, and of related conditions (associated with gastrointestinal stromal tumors [GIST]). In the course of our work, we identified a patient with a new syndrome, known as the paraganglioma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome (or Carney-Stratakis syndrome), for which we found mutations in the genes encoding succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunits A, B, C, and D. In another patient, we found a novel germline mutation in the tyrosine kinase–encoding PDFGRA gene. In collaboration with a group in Germany, we identified an epigenetic defect (methylation of the SDHC gene) that may be used diagnostically to identify patients with the Carney Triad.

Clinical investigations into the diagnosis and treatment of adrenal and pituitary tumors

Patients with adrenal tumors and other types of Cushing’s syndrome (and occasionally other pituitary tumors) come to the NIH Clinical Center for diagnosis and treatment. Ongoing investigations focus on:

- the prevalence of ectopic hormone receptor expression in adrenal adenomas and PMAH/MMAD;

- the diagnostic use of high-sensitivity magnetic resonance imaging for earlier detection of pituitary tumors; and

- the diagnosis, management, and postoperative care of children with Cushing’s syndrome and other pituitary tumors.

Clinical and molecular investigations into other pediatric genetic syndromes

Mostly in collaboration with several other investigators at the NIH and elsewhere, we are conducting work on pediatric genetic syndromes seen in our clinics and wards. One such example is the recent identification of SGPL1 defects in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency.

Additional Funding

- INSERM, Paris, France (Co-Principal Investigator): “Clinical and molecular genetics of Carney complex,” 06/2003–present

- Several small grants supporting staff members from France, Brazil, Greece, Spain, and elsewhere

- Bench-to-Bedside 2017 Award: “Therapeutic targets in African Americans with primary aldosteronism”

- Gifts on Cushing's syndrome research (various private donations)

- Pfizer #W1215907 2017–2018 US ASPIRE ENDOCRINE study titled “Characterization of GPR101-mediated growth regulation and receptor deorphanization”

- Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences 2018 Award “Genetics of human susceptibility to infections and/or complications of Zika virus: variants of the cyclic AMP-dependent PKA pathway”

Publications

- London E, Wester JC, Bloyd MS, Bettencourt S, McBain CJ, Stratakis CA. Loss of habenular Prkar2a reduces hedonic eating and increases exercise motivation. JCI Insight 2020;5(23):141670.

- Drougat L, Settas N, Ronchi CL, Bathon K, Calebiro D, Maria AG, Haydar S, Voutetakis A, London E, Faucz FR, Stratakis CA. Genomic and sequence variants of protein kinase A regulatory subunit type 1β (PRKAR1B) in patients with adrenocortical disease and Cushing syndrome. Genet Med 2020;23:174–182.

- Espiard S, Drougat L, Settas N, Haydar S, Bathon K, London E, Levy I, Faucz FR, Calebiro D, Bertherat J, Li D, Levine MA, Stratakis CA. PRKACB variants in skeletal disease or adrenocortical hyperplasia: effects on protein kinase A. Endocr Relat Cancer 2020;27(11):647–656.

- Schernthaner-Reiter MH, Trivellin G, Roetzer T, Hainfellner JA, Starost MF, Stratakis CA. Prkar1a haploinsufficiency ameliorates the growth hormone excess phenotype in Aip-deficient mice. Hum Mol Genet 2020;29(17):2951–2961.

- Tirosh A, RaviPrakash H, Papadakis GZ, Tatsi C, Belyavskaya E, Charalampos L, Lodish MB, Bagci U, Stratakis CA. Computerized analysis of brain MRI parameter dynamics in young patients with Cushing syndrome-a case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105(5):e2069–e2077.

- Maria AG, Suzuki M, Berthon A, Kamilaris C, Demidowich A, Lack J, Zilbermint M, Hannah-Shmouni F, Faucz FR, Stratakis CA. Mosaicism for KCNJ5 causing early-onset primary aldosteronism due to bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia. Am J Hypertens 2020;33(2):124–130.

Collaborators

- Albert Beckers, MD, Université de Liège, Liège, Belgium

- Jerome Bertherat, MD, PhD, Service des Maladies Endocriniennes et Métaboliques, Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France

- Sosipatros Boikos, MD, Medical College of Virginia, Medical Oncology, Richmond, VA

- Stephan Bornstein, MD, PhD, Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

- Isabelle Bourdeau, MD, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada

- J. Aidan Carney, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

- Nickolas Courkoutsakis, MD, PhD, University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, Greece

- Jacques Drouin, PhD, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada

- Jennifer Gourgari, MD, Georgetown University, Washington, DC

- Margaret F. Keil, PhD, RN, CRNP, Office of the Clinical Director, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Lawrence Kirschner, MD, PhD, James Cancer Hospital, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

- Andre Lacroix, MD, PhD, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada

- Giorgios Papadakis, MD, MPH, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece

- Nickolas Patronas, MD, Diagnostic Radiology, Clinical Center, NIH, Bethesda, MD

- Erwin Van Meir, PhD, Emory University, Atlanta, GA

- Antonios Voutetakis, MD, PhD, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Contact

For more information, email stratakc@mail.nih.gov or visit https://segen.nichd.nih.gov.