Mechanisms Regulating GABAergic Cell Development

- Timothy J. Petros, PhD, Head, Unit on Cellular and Molecular Neurodevelopment

- Yajun Zhang, BM, Biologist

- Dongjin Lee, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Chris Rhodes, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow

- Dhanya Asokumar, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Lielle Elisha, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Daniel Lee, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Rahul Maini, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

- Ava Papetti, BS, Postbaccalaureate Fellow

The incredible diversity and heterogeneity of interneurons was observed over a century ago, with Ramon y Cajal hypothesizing in “Recollections of My Life” that “the functional superiority of the human brain is intimately linked up with the prodigious abundance and unaccustomed wealth of the so-called neurons with short axons.” Although interneurons constitute the minority (20%) of neurons in the brain, they are the primary source of inhibition and are critical components in the modulation and refinement of the flow of information throughout the nervous system. Abnormal development and function of interneurons has been linked to the pathobiology of numerous brain diseases, such as epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism. Interneurons are an extremely heterogeneous cell population, with distinct morphologies, connectivities, neurochemical markers, and electrophysiological properties. With the advent of new technologies such as single-cell sequencing to dissect gene expression and connectivity patterns, the classification of interneurons into specific subtypes is ever evolving.

Interneurons such as GABAergic projection neurons are born in the ventral forebrain during embryogenesis and undergo a prolonged migratory period to populate nearly every brain region. However, our general understanding of the developmental mechanisms that generate such GABAergic cell diversity remains poorly understood. The goal of our lab is to dissect the genetic and molecular programs that underlie initial fate decisions during embryogenesis and to explore how the environment and genetic cascades interact to give rise to such a stunning diversity of GABAergic cell subtypes. We take a multifaceted approach, utilizing both in vitro and in vivo strategies to identify candidate mechanisms that regulate interneuron fate decisions. We strive to develop cutting-edge techniques that will overcome the many challenges faced when studying interneuron development. We believe that our pursuits will act as a springboard for future research and provide new insights into both normal development and various neurodevelopmental diseases.

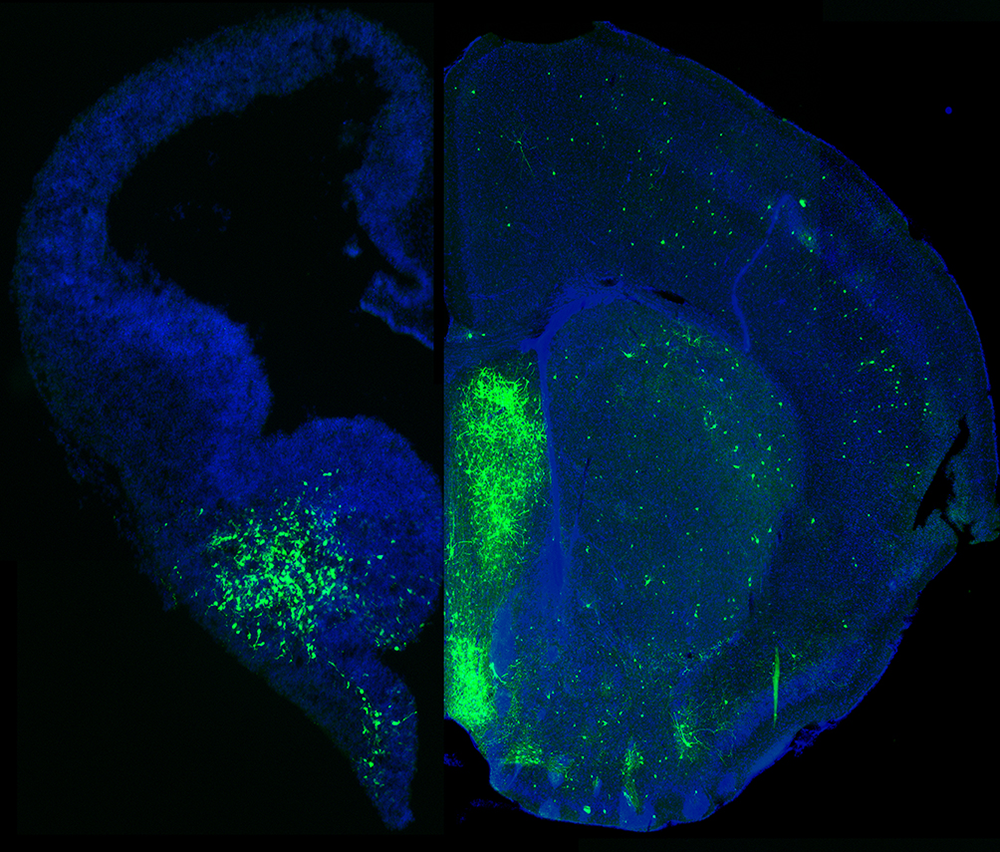

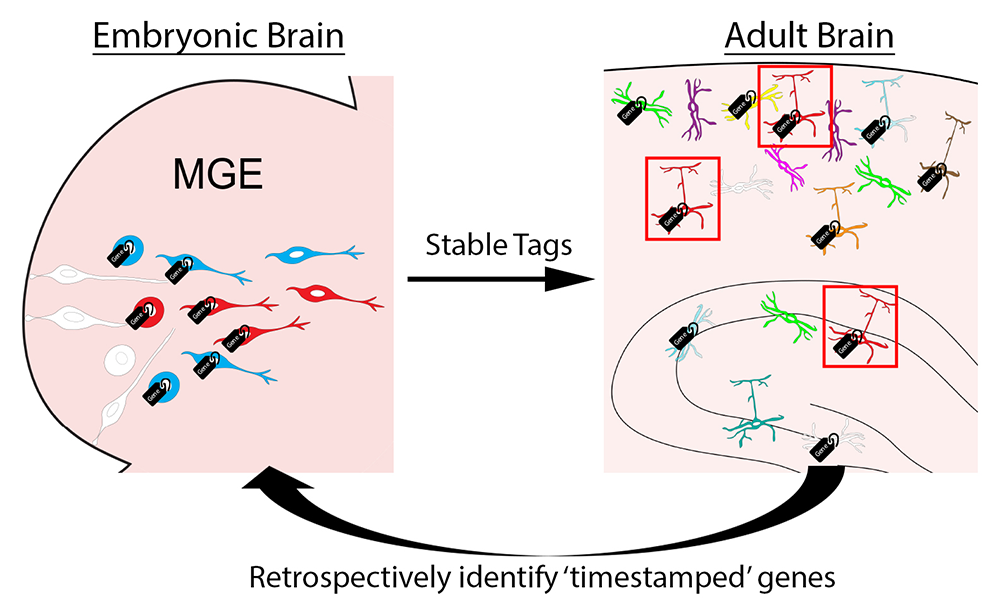

Figure 1. MGE–derived GABAergic cells populate many different brain regions.

The image depicts a section of an embryonic brain (left) that has been electroplated to label cells derived from the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE), merged with an section of an adult brain (right), displaying the incredible spatial and morphological diversity of MGE–derived cells in the mature brain. Understanding how this heterogeneous population is generated from one embryonic brain structure is the focus of this laboratory.

Mechanisms regulating initial fate decisions within the medial ganglionic eminence

The medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) gives rise to the majority of forebrain interneurons, most notably the somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing (SST+ and PV+) subtypes, and some nNOS (neuronal nitric oxide synthetase)–expressing neurogliaform and ivy cells in the hippocampus. The MGE is a transient, dynamic structure that arises around E10 and bulges into the lateral ventricle over the next several days before dissipating towards the end of embryogenesis. Given that initial fate decisions are generated within the MGE, there has been much focus on identifying a logic for interneuron generation from this region. Previous experiments characterized both a spatial and temporal gradient within the MGE, which regulates the initial fate decision to become either PV+ or SST+ interneurons. SST+ interneurons are preferentially born early in embryogenesis from the dorsoposterior MGE, whereas PV+ interneurons are born throughout embryogenesis with a bias of originating from the ventroanterior MGE.

We discovered an additional mechanism regulating this fate decision: the mode of neurogenesis. Using in utero electroporations, we found that PV+ interneurons are preferentially born from basal progenitors (also known as intermediate progenitors), whereas SST+ interneurons arise more commonly from apical progenitors. We hope to build on this observation to discover how these distinct spatial, temporal, and neurogenic gradients are coordinated to regulate initial fate decisions of MGE progenitors. To this end, we performed a comprehensive single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) analysis of ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ) cells throughout the mouse embryonic forebrain. This allows us to compare gene expression profiles both between distinct brain regions [MGE, lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE), cortex)] and within specific subdomains of these regions (dorsal vs. ventral LGE).

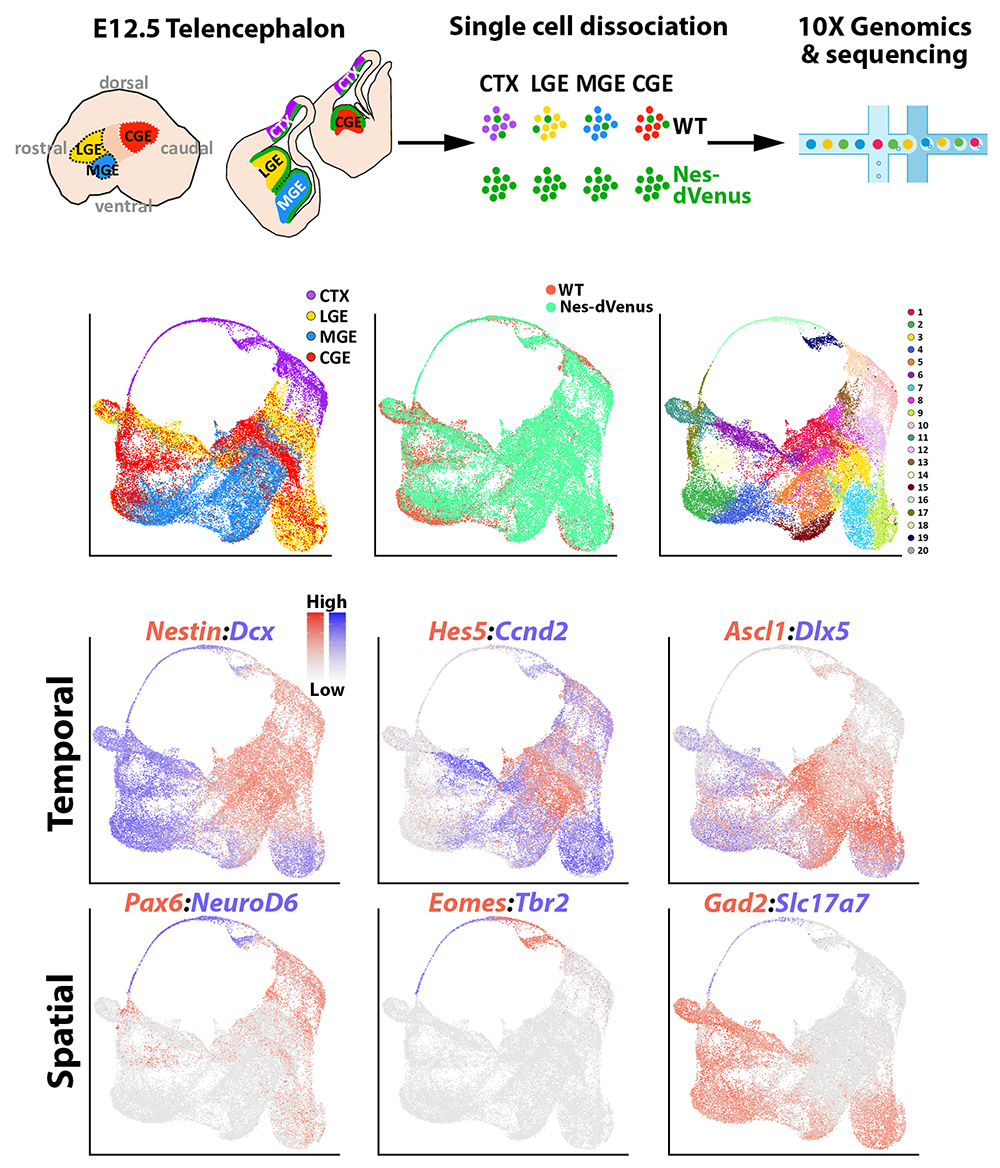

Figure 2. Single-cell sequencing in the embryonic mouse forebrain

Top row. Experimental paradigm to harvest cells from four distinct brain regions (MGE, LGE, CGE, cortex) from WT and Nestin-dVenus embryonic mouse brains for single-cell RNA-sequencing.

Middle row. UMAP plots of single cells categorized by brain region (left), mouse line (middle), or putative cell cluster (right).

Bottom rows. UMAP plots depicting gene expression profiles enriched in different stages of neural progenitors (top) or spatial domains (bottom).

Characterization of the epigenetic landscape during embryonic neurogenesis

In multicellular organisms, cells are genetically homogenous but structurally and functionally heterogeneous as a result of differential gene expression, which is often mitotically heritable. The mechanisms regulating such expression are ‘epigenetic,’ as they do not involve altering the DNA sequence itself; they include DNA methylation (DNAme), histone modifications, and higher-order chromatin structure. In particular, DNA and histone modifications often follow specific rules termed the ‘epigenetic code,’ similar to the genetic code. Collectively, DNAme and histone modification have been reported to regulate transcription and chromatin structure in many stem-cell and developmentally critical processes. Previous scRNA-Seq experiments on the ganglionic eminences (GEs) identified surprisingly few region-specific genes in cycling progenitors (immature cells that are still cycling and have not exited the cell cycle), despite the fact that these regions produce distinct GABAergic cell populations. Because there are dynamic changes in the chromatin landscape during development, a prevailing hypothesis is that epigenomic signatures may be a better predictor of cell fate during development, revealing both potential distal enhancers and/or genetic loci that may be ‘poised’ but not yet expressed. However, direct support for this hypothesis is lacking. The idea is particularly relevant, given that epigenetic changes are observed in many neurological and psychiatric diseases and that most single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) identified in diseases-specific genome-wide association studies (GWAS) map to non-coding regions, implying that epigenetic regulation of gene expression may underlie some disease etiologies.

We performed single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (scATAC-Seq) in combination with Cut&Tag, also known as cleavage under targets and tagmentation, and Capture-C, a high-throughput approach to analyze cis interactions, in order to define the ground truth chromatin state in distinct embryonic brain regions. We are currently expanding on this knowledge to determine how such chromatin and epigenetic organization is disrupted in various gene mutations.

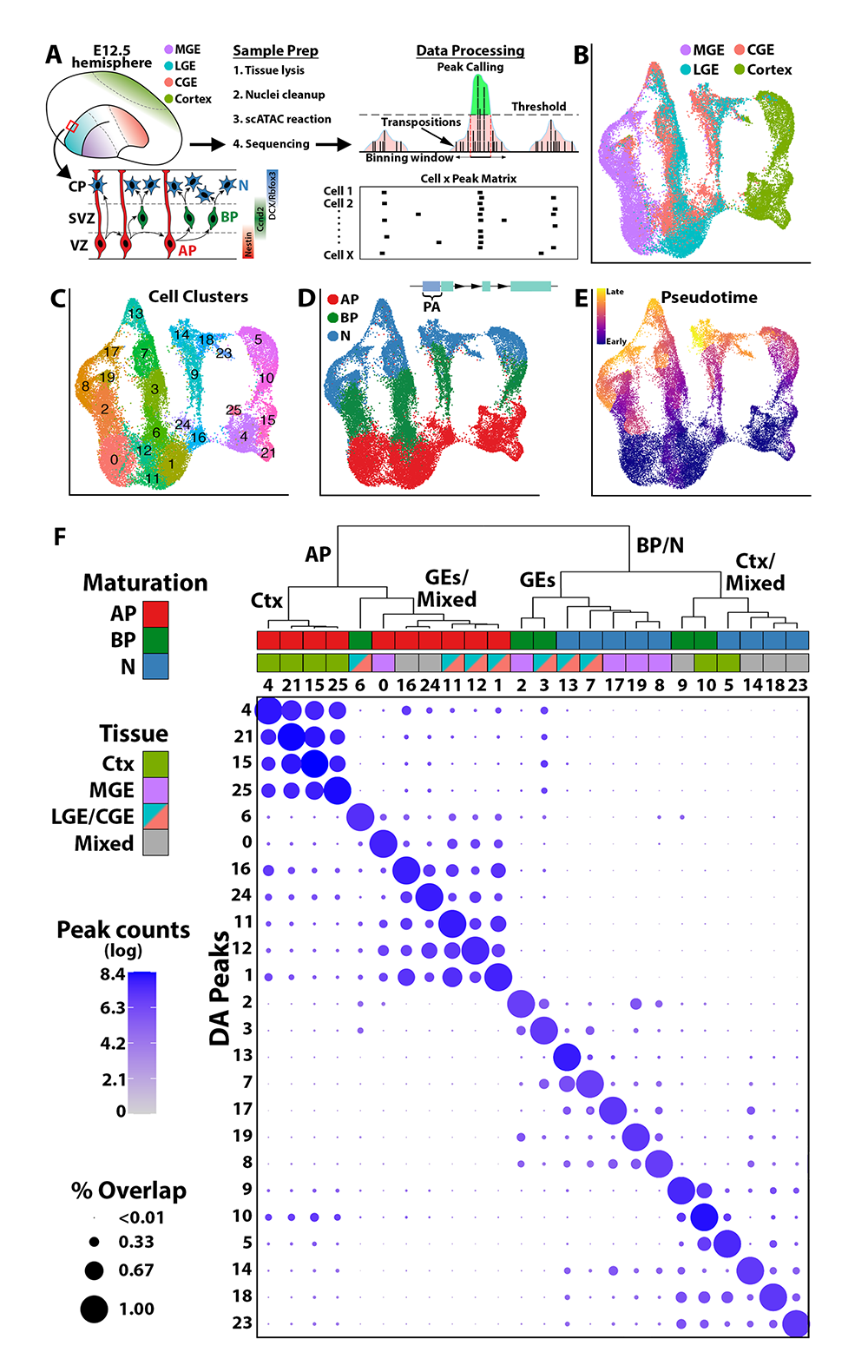

Figure 3. snATAC-Seq in distinct regions of the mouse embryonic forebrain

A. Schematic of snATAC-Seq (single-nucleus analysis of transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing) workflow and neurogenic cell types: apical progenitors (APs), basal progenitors (BPs) and neurons (Ns). B-E. UMAP visualization of single nuclei clustered by brain region (B), SLM (C), neurogenic cell type (D), and pseudotime (E). In (D), PA = promoter accessibility, representing reads mapping within 2 kb upstream of TSSs. F. Embryonic snATAC-Seq dot plot of differentially accessible peaks (DA peaks) for each cluster. Dot diameter indicates the percent of DA peaks from one cluster (column cluster labels) that are detectable in any other cluster (row cluster labels). Color intensity represents the total DA peak count per cluster. Hierarchical clustering was performed using correlation distance and average linkage.

How the environment sculpts interneuron diversity and maturation.

Interneurons undergo an extensive tangential migration period before reaching their terminal brain region, whereupon they interact with the local environment to differentiate and mature. The composition of interneuron subtypes varies significantly between different brain regions. Numerous experiments indicate that general interneuron classes, e.g., PV+– or SST+–expressing interneurons, are determined as cells become post-mitotic during embryogenesis. However, when other features that define a mature interneuron subtype (neurochemical markers, cell type and subcellular location of synaptic partners, electrophysiology properties, etc.) are established remains unknown. One hypothesis is that interneurons undergo an initial differentiation into ‘cardinal’ classes during embryogenesis, and that maturation into ‘definitive’ subgroups requires active interaction with their mature environment. An alternative hypothesis is that immature interneurons are already genetically hardwired into definitive subgroups, and that the environment more passively sculpts the maturation of these cells.

To test these competing hypotheses, we are harvesting early postnatal interneuron precursors (P0–P2) in specific brain regions and transplanting them into wild-type hosts either homotopically (cortex-to-cortex) or heterotopically (cortex-to-hippocampus or cortex-to-striatum). The technique allows us to determine whether transplanted interneurons adopt properties of the host environment (indicating a strong role for the environment in regulating interneuron diversity) or retain subtype features more consistent with the donor region. Our initial experiments indicate that the environment largely determines the composition of interneuron subtypes in a brain region, regardless of donor region. However, some interneuron subtypes appear to be more genetically predefined and resistant to environmental influences than others. We are currently following up on these studies using scRNA-Seq to characterize, in an unbiased manner, how a cell's transcriptome is altered when grafted into a new brain environment.

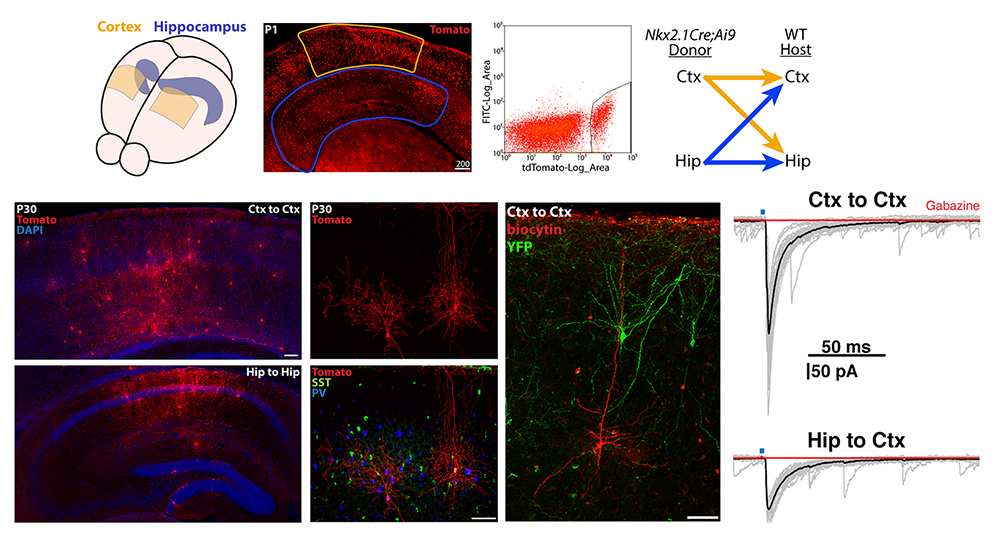

Figure 4. Transplantation of MGE–derived interneuron precursors into postnatal brains

Top. MGE–derived interneuron precursors are harvested from the cortex and hippocampus of P1 Nkx2.1-Cre;Ai9 mice, FACS–purified, and transplanted either homotopically (Ctx-to-Ctx, Hip-to-Hip) or heterotopically (Ctx-to-Hip, Hip-to-Ctx) into P1 wild-type (WT) mice.

Bottom. 30 days post-transplantation, tomato+ cells are dispersed throughout the host regions, displaying morphologies and neurochemical markers similar to endogenous interneurons. Grafted interneurons integrate into the host circuitry, as indicated by the postsynaptic responses in pyramidal cells upon stimulation of adjacent Nkx2.1-Cre;Ai32–derived, channel rhodopsin–expressing interneurons. Ctx: cortex; Hip: hippocampus.

Novel approach to identifying genetic cascades underlying interneuron fate decisions

The ability to longitudinally track gene expression within defined populations is essential for understanding how changes in expression mediate both development and plasticity. Previous screens that were designed to identify genes and transcription factors specific to SST– or PV–fated interneurons were largely unsuccessful because several issues significantly hinder these types of studies. First, such interneurons originate from the MGE, which is a heterogeneous population of progenitors that give rise to both interneurons and a variety of GABAergic projection neurons, making it difficult to separate interneuron progenitors from other cell types. Additionally, many markers that define mature interneuron subtypes are not expressed embryonically, and thus the class-defining markers are not helpful for studying MGE progenitors.

In an ideal scenario, we would like to identify actively transcribed genes in MGE progenitors undergoing fate decisions while retaining the capacity to identify whether such cells become PV– or SST–expressing interneurons in the postnatal brain. To this end, we are developing a spatially and temporally inducible form of DNA adenine methylase identification (DamID), which will allow us to label the transcriptome of MGE progenitors. Once we have the tools to distinguish between specific interneuron cell types, labeled cells can be harvested at maturity. Then, the methylated genomic DNA will be analyzed, allowing us to look back in time to identify candidate fate-determining genes expressed in specific interneuron populations. Our hope is that the strategy could be widely applicable, so that an investigator could characterize the temporal gene-expression pattern of the cell type of interest.

Figure 5. Timestamp of actively transcribed genes during development for future analysis

The goal of this approach is to label actively transcribed genes with stable methylation tags during embryogenesis as progenitors are undergoing initial fate decisions in the MGE. We can then harvest specific interneuron subtypes in the adult brain using various transgenic mouse lines. Retrospective identification of an actively transcribed gene during embryogenesis will provide us with candidate fate-determining genes for specific interneuron subtypes.

Additional Funding

- NICHD Scientific Director’s Award

Publications

- Rhodes CT, Mitra A, Lee DR, Lee DJ, Zhang Y, Thompson JJ, Rocha PP, Dale RK, Petros TJ. Single cell chromatin accessibility reveals regulatory elements and developmental trajectories in the embryonic forebrain. BioRxiv 2021; https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.21.436353.

- Lee DR, Rhodes CT, Mitra A, Zhang Y, Maric D, Dale RK, Petros TJ. Transcriptional heterogeneity of ventricular zone cells throughout the embryonic mouse forebrain. BioRxiv 2021; https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.05.451224.

- Alkaslasi MR, Piccus ZE, Hareedran S, Silberberg H, Chen L, Zhang Y, Petros TJ, Le Pichon CE. Single nucleus RNA-sequencing defines unexpected diversity of cholinergic neuron types in the adult mouse spinal cord. Nat Commun 2021;12:2471.

- Mahadevan V, Mitra A, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Peltekian A, Chittajallu R, Esnault C, Maric D, Rhodes C, Pelkey KA, Dale R, Petros TJ, McBain CJ. NMDARs drive the expression of neuropsychiatric disorder risk genes within GABAergic interneuron subtypes in the juvenile brain. Front Mol Neurosci 2021;14:712609.

- Murillo A, Navarro AI, Puelles E, Zhang Z, Petros TJ, Perez-Otano I. Temporal dynamics and neuronal specificity of Grin3a expression in the mouse forebrain. Cereb Cortex 2021;3(4):1914–1926.

Collaborators

- Ryan Dale, PhD, Bioinformatics Core, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Claire Le Pichon, PhD, Unit on the Development of Neurodegeneration, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Chris McBain, PhD, Section on Cellular and Synaptic Physiology, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

- Isabel Perez-Otano, PhD, Instituto de Neurociencias de Alicante, Alicante, Spain

- Pedro Rocha, PhD, Unit on Genome Structure and Regulation, NICHD, Bethesda, MD

Contact

For more information, email tim.petros@nih.gov or visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/atNICHD/Investigators/petros.